Looking for older blog posts? Check out our Blog Archive!

Alaska State Parks Blog

2025

-

Coastal Connections Kids Camp, 2025 at Caines Head State Recreation Area, August, 2025 - Kendra Warlow

-

On July 25th, 2025, Coastal Connections Kids Camp put on by KMTA (Kenai Mountain Turnagain Arm National Heritage Area) came out to visit and learn about our Historic Fort McGilvary at Caines Head State Recreation Area. The kids had a guided hike up Road No. 1 (Fort Trail), stopping to read the dedication for the 250th and 267th Coast Artillery Battalions who served at Fort McGilvray, and inside War Reserve Magazine B for a history talk given by our Volunteer-In-Parks, Kendra Warlow.

The kids helped Kendra place the first of many new signs along the Fort Trail so future visitors can learn what types of buildings were standing during World War II. They found the sign location by using latitude and longitude and practicing with a GPS.

Finally, the kids made it up to Battery 293! They had a blast adventuring around through the rooms and trying to place themselves in the shoes of the men who served there.

We’re pleased to connect again with KMTA as several years ago we partnered with them to place our permanent interpretive signs on the grounds of Fort McGilvray and Battery 293!

-

-

From Estuary to Bog: Reflections from Ernest Gruening State Historic Park and Point Bridget State Park

Art by McKenna Dickerson and Nina Grauley. Text by Matthew Dickerson-

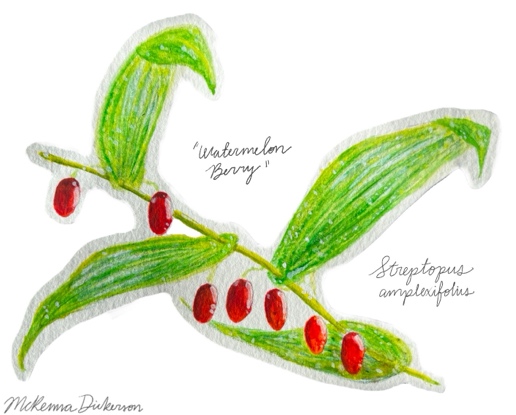

It’s 5:00am on August 2, the second morning of a two-week collaborative artist residency with my daughter-in-law McKenna at Eaglerock Cabin in Ernest Gruening State Historic Park. My internal clock is still in Vermont where it’s now 9:00am, so I’ve been awake for a while. But it’s already light outside–a reminder of long Alaska summer days even in the southeast part of the state. So I rise, don sweatpants and a jacket, and head outside. I walk down to the rocky shoreline, making my way past dark ripe gooseberries on their spiky vines, small patches of watermelon berries low to the ground near the trees, blueberries, and red huckleberries toward where Peterson Creek tumbles down a series of small cascades from the pond known as the Peterson Salt Chuck into the far saltier water of Amalga Bay.

On an exceptionally high tide—an event that happens only four or five times a year, I’ve been told—the cascades cease to exist and the ocean flows back into the pond. Technically, this periodic influx of saltwater makes the pond a lagoon, giving it a permanent layer of brackish saltwater on the bottom with a habitat that supports various marine creatures, while a steady influx of river water from Peterson Creek tumbling down off the hills in the Tongass National Forest keeps a top layer fresh where cutthroat trout and Dolly Varden char swim.

On an exceptionally high tide—an event that happens only four or five times a year, I’ve been told—the cascades cease to exist and the ocean flows back into the pond. Technically, this periodic influx of saltwater makes the pond a lagoon, giving it a permanent layer of brackish saltwater on the bottom with a habitat that supports various marine creatures, while a steady influx of river water from Peterson Creek tumbling down off the hills in the Tongass National Forest keeps a top layer fresh where cutthroat trout and Dolly Varden char swim.

At present, the tide is out and the water is falling almost twenty feet from pond to ocean. A metaphoric quiet pervades the place, especially in the early hours when I am the only human about. But it is not at all quiet in the literal sense. In addition to the rumble of the waterfall and the lapping of waves on rocks, I hear a chattering of Stellar jays and the constant squawking of gulls and crows that circle looking for food scraps on the exposed intertidal zone. Now and then, one of the bald eagles responds to the ruckus with its piercing high-pitched cry. There always seem to be a few eagles hanging out in the tall spruce that circle the bay or—as the name of the iconic cabin suggests—perched atop large rocks closer to the water and their food. And there is plenty of food around for a hungry eagle, crow, or gull.

In the summer, that abundant food is mostly salmon and their eggs. At present, chum salmon—also known as keta, silverbrite, and dog salmon—are trying to swim up Peterson Creek. Their dead carcasses are everywhere. So is their smell. But despite their irresistible urge to spawn, they can’t make it beyond the top of the falls and into the Salt Chuck because a grate blocks the mouth of the pond. The pool below the grate is so packed with salmon trying vainly to get through that it looks like a sardine can.

It took me a day to get the story behind the grate. Although numerous species of salmon including chum as well as ocean-run cutthroat trout and Dolly Varden char are native to the wider Juneau area, chum are not among the species naturally found in Peterson Creek. In order to support the commercial fishery, they were raised by a hatchery and released as fry into the waters of Amalga Bay. They mostly live lives similar to those of their wild salmon cousins: hunting for food in coastal waters while trying to avoid the many creatures that want to hunt them. After a few years in the ocean (typically four or five for a chum salmon, but as few as three and as many as six) when their spawning season comes (July for chum salmon), the hatchery puts a temporary grate across the river in order to prevent them from entering the creek in large numbers, which could potentially upset the ecological balance of a river where they are not native. In a couple weeks, when the chum are almost gone, the grate will come down to allow other salmon species that are native to Peterson Creek to migrate in: first the pink salmon (a.k.a. humpies) in early August, and then later in the summer the run of silvers (coho).

It took me a day to get the story behind the grate. Although numerous species of salmon including chum as well as ocean-run cutthroat trout and Dolly Varden char are native to the wider Juneau area, chum are not among the species naturally found in Peterson Creek. In order to support the commercial fishery, they were raised by a hatchery and released as fry into the waters of Amalga Bay. They mostly live lives similar to those of their wild salmon cousins: hunting for food in coastal waters while trying to avoid the many creatures that want to hunt them. After a few years in the ocean (typically four or five for a chum salmon, but as few as three and as many as six) when their spawning season comes (July for chum salmon), the hatchery puts a temporary grate across the river in order to prevent them from entering the creek in large numbers, which could potentially upset the ecological balance of a river where they are not native. In a couple weeks, when the chum are almost gone, the grate will come down to allow other salmon species that are native to Peterson Creek to migrate in: first the pink salmon (a.k.a. humpies) in early August, and then later in the summer the run of silvers (coho).

While I haven’t come down this morning to look at nearly-dead salmon, it is partly because of them that I came. I’m hoping to see the sow black bear with two spring cubs that has been a regular visitor to the pool, taking advantage of the easy food source. She doesn’t even need to open the sardine can. The fish have nowhere to go to escape her. And I know, by the appearance of a fresh pile of her scat and a couple more half-eaten salmon carcasses on the shore, that she has visited at some point in the last twelve hours. The thought that a sow bear with cubs might be present is one reason I am walking out in the open on the rocks, and not coming through the trees.

the appearance of a fresh pile of her scat and a couple more half-eaten salmon carcasses on the shore, that she has visited at some point in the last twelve hours. The thought that a sow bear with cubs might be present is one reason I am walking out in the open on the rocks, and not coming through the trees.

Although the sow and cubs do not appear this morning, I haven’t been there three minutes when I see a lone male black bear in the pool, just 30 yards away. I watch for a while from a distance, standing atop a tall rock down close to the tidewater. The food is so plentiful and easy that the bear doesn’t have to stay long. Soon, it has had its fill and disappears into brush on the same side of the river I am on. I continue to watch the pool from down on the rocks, waiting for the bear to reemerge, until I realize it has circled around behind me—likely to avoid human interaction—and popped out of the woods thirty yards behind me. I watch it wander on down the beach past the cabin and around the point.

Unfortunately, the previous day somebody saw one of the bears at the same spot, got spooked, and emptied their can of bear spray. Then they left the can lying on the ground. And that, as Ranger Garasky told me when he stopped by the cabin for a visit, was why he did not shake my hand. He’d just been handling the can and didn’t want to get any chemicals on me.

⚫

Brad Garasky is not only the Chief Ranger for all the Alaska State Parks in the southeast district; he is the only ranger for the parks in the Juneau area. His territory includes several road-access parks, a number of boat-access marine parks, and also numerous hiking-trail corridors that are not part of named parks. Considering the size of that range, he has his work cut out for him. So you might think that on his days off, the last thing he'd want to do is go to one of those parks. For him, it could be too much like going to work. But as we sat and talked, he told me that the state parks are his favorite places to spend his time off. And I had good reason to believe him. I’d first met Brad nearly two years early in September of 2022

while hiking a trail to Cowee Meadow in Point Bridget State Park. And, yes, that had been on his day off. I was hiking the opposite direction when we passed, but we stopped and talked for a bit. I had a few questions about the area—including wondering about the best way to get across the meadow to Cowee Creek so I could do a little fishing—and I'd fortuitously bumped into the best possible person to ask.

while hiking a trail to Cowee Meadow in Point Bridget State Park. And, yes, that had been on his day off. I was hiking the opposite direction when we passed, but we stopped and talked for a bit. I had a few questions about the area—including wondering about the best way to get across the meadow to Cowee Creek so I could do a little fishing—and I'd fortuitously bumped into the best possible person to ask.

Two years later, and I was back in the Juneau for another artist residency with my daughter-in-law McKenna. On our first full day, Brad popped in to visit and see how we were doing—this time on duty and in uniform. We talked about the bear and the empty can of bear spray, both of us conjecturing that it was very unlikely somebody actually needed to spray it since the bears have been coming to that spot for days, ignoring the numerous human visitors to the park, eating a quick meal, and peacefully disappearing with no previous signs of aggression. That made us both feel sad for the unnecessary trauma to the bear.

Then we talked about why Brad appreciates the state parks so much and spends even his off-duty time in them. His list included the diversity of the parks in the area: cultural-historical diversity, ecological diversity, and the diversity of opportunities. "There's something for everybody," he says. "Culture. Hiking. Fishing. Boating. Even learning how to live off the land from the traditions of native peoples who have been doing it for centuries." He notes that while commercial harvesting is not allowed on state parks lands, harvesting for personal consumption is, whether for fish or berries. There is obvious delight in his face and voice as he says all this. He also points out that nearby Eagle Beach State Recreation Area (also part of the state park system) offers handicap access.

The conversation prompts me to think of the historic significance of the cabin where I am staying, knowing that it was here that Ernest Gruening—once Governor of the territory of California—wrote many of the magazine articles as well as his book The State of Alaska that would help lead to the Alaska territory become a state in which Gruening would serve two terms as senator. Gazing out at the surrounding beauty, I can see why Gruening was so inspired. I think also of the many prominent public figures such as Adlai Stevenson and Justice William O. Douglas who visited Gruening at the cabin, and experienced the same inspiration. I would have liked to listen in to some of the conversations that took place within the walls. Did they talk politics? Or fishing? Learning that Ernest and his wife Dorothy were regular swimmers in Amalga Bay gives me an even greater appreciation for them—though as I stood in the chilly water a couple days later to cast flies for salmon, I was not tempted to try a swim even in August.⚫

A week later, my wife Deborah and a young artist friend named Nina Grauley join McKenna and me for a few days. One morning, we drive up to Point Bridge State Park. After spending some time on Cowee Creek which runs along part of the park's eastern boundary, catching a few Dolly Varden char while watching spawning salmon swim past, we start down the trail that leads to Cowee Meadow where one of park’s two cabins sits. We don’t get very far, though.

A week later, my wife Deborah and a young artist friend named Nina Grauley join McKenna and me for a few days. One morning, we drive up to Point Bridge State Park. After spending some time on Cowee Creek which runs along part of the park's eastern boundary, catching a few Dolly Varden char while watching spawning salmon swim past, we start down the trail that leads to Cowee Meadow where one of park’s two cabins sits. We don’t get very far, though.

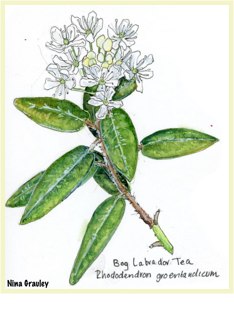

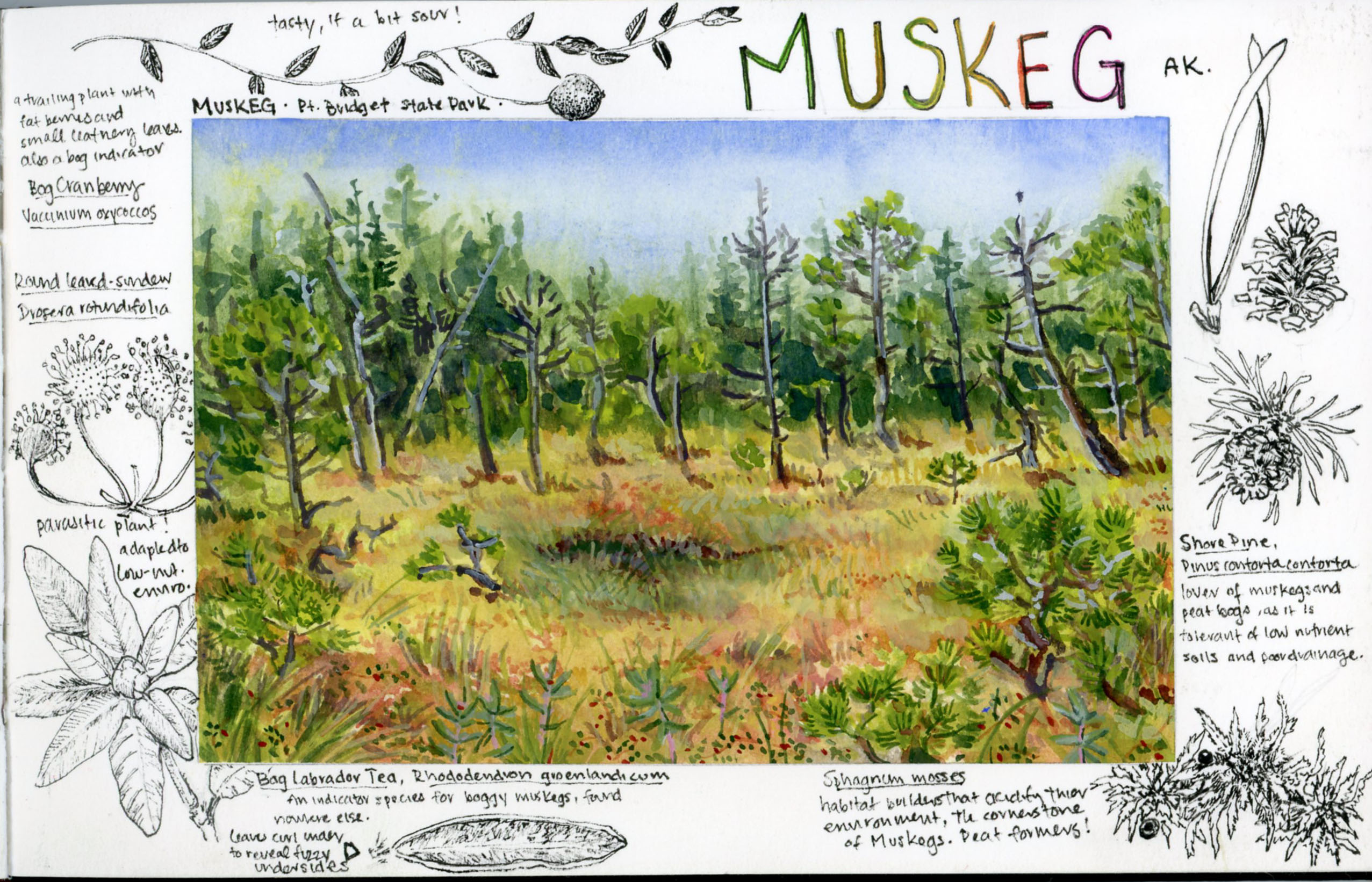

Nina, who works as a scientific illustrator as well as an artist, has a lifelong love of bogs—or muskegs as the North American version of bogs are called. Characterized by water that doesn't visibly flow anywhere, mixed with dead vegetation, and covered over with moss, they are wonderfully fascinating ecosystems with many unique plants that thrive in acidic soil through unique adaptations such those of carnivorous plants which get their nutrients by eating insects.

Not more than a couple hundred yards down the trail, Nina is suddenly on her hands and knees letting out exuberant exclamations of delight and wonder. Soon I’m kneeling beside her asking her what she has found. Every few inches along the moss she seems to find another unique plant. "Bog Laurel," she says excitedly, pointing out a pretty little plant no more than a foot tall with four or so opened pink and red blossoms. She will later look up the specific species of the variety found at Point Bridget: Kalmia microphylla. And then she calls me over to see some Bog Rosemary, whose leaves stand upright but whose white and pink bell-like blossoms droop to the ground. And so it goes. Not surprisingly, many of the plants she identifies have a name beginning with the word "bog" or "swamp" (though as Nina points out to me, a bog and a swamp are very different things!)

later look up the specific species of the variety found at Point Bridget: Kalmia microphylla. And then she calls me over to see some Bog Rosemary, whose leaves stand upright but whose white and pink bell-like blossoms droop to the ground. And so it goes. Not surprisingly, many of the plants she identifies have a name beginning with the word "bog" or "swamp" (though as Nina points out to me, a bog and a swamp are very different things!)

She is especially excited to find a species of sundew, since it’s a carnivorous plant. With roots unable to get nutrients from the acidic soil, its strategy is to attract insects with a sugary goo on its leaves, then to trap them with tentacles and dissolve them to extract needed proteins. Like something out of a horror movie, but a lot smaller.

Now and then she will point to something larger that I don’t need to be on my knees to see, like the Shore Pines that sparsely dot the area. Or she’ll point out a plant that is actually familiar to me, like the Bog Cranberry plants. I begin to feel her excitement spreading over to me—though perhaps not as great as my own excitement had been an hour earlier holding a chrome-bright Dolly Varden char with its characteristic pinkish—purpose spots that had likely only recently moved up out of the ocean into Cowee Creek to feed on salmon eggs.

And I think again of my conversation several days earlier with ranger Brad Garasky about how much the parks in the area have to offer visitors. I have now added "bogs and really cool bog plants" to the list of attractions.

Muskeg, Point Bridget State Park, by Nina Grauley⚫

About the Artists: McKenna Dickerson and her father-in-law Matthew Dickerson were collaborative artists-in-residence for Alaska State Parks in August of 2024, where they enjoyed a visit from fellow artist Nina Grauley. McKenna Dickerson (https://www.mckennadickerson.com/") is a Vermont-based artist, maker, and naturalist. She received her BFA from Saint Michael's College where she pursued art & design and environmental studies. As a painter and mixed-media artist, McKenna explores human relationships with the environment. Her artwork focuses on unique textures, colors, and form in nature as a way of drawing attention to, celebrating, and learning about the world around us that we often overlook. Author Matthew Dickerson (www.matthewdickerson.net and www.troutdownstream.net) has published several books of creative narrative non-fiction related to nature, outdoors, and environment, and his essays have appeared in numerous journals and magazines. His books with settings in Alaska include Birds in the Sky, Fish in the Sea: Attending to Creation with Wonder and Delight (Square Halo Books, 2025), The Salvelinus, the Sockeye, and the Egg-Sucking Leech: Abundance and Diversity in the Bristol Bay Drainage (Wings Press, 2023), and The Voices of Rivers: Reflections on Places Wild and Almost Wild (Homebound Publications, 2019). He has also published historical fiction and fantasy literature. He teaches at Middlebury College in Vermont. Nina Grauley (https://ninagrauley.com/) is a science illustrator, artist, and enthusiastic amateur naturalist. Her work is centered around the idea that paying attention is an act of love. She believes that looking closely at nature can teach us more about what it means to be human, and how we can begin the process of healing together.

-

2024

-

Adventure in Thumb Cove: Porcupine Cabin - Kate Ayers, June 2024

-

Having ventured through over 45 Alaska Public Use Cabins, the quest for a new cabin close to Anchorage was proving to be a challenging task. Therefore, the moment I noticed an opening for the Porcupine Cabin during the early summer period, I seized the opportunity and booked it without hesitation.

Porcupine Cabin is one of two cabins in Thumb Cove, outside of Seward Alaska. I visited Spruce Cabin, a short walk on the beach from Porcupine Cabin, nearly 10 years ago – it was time to explore Thumb Cove again. Both of the Thumb Cove cabins are tucked a little further in from the beach, surrounded by what my kids lovingly refer to as the "Dr. Seuss Forest," thanks to its whimsically shaped trees.

Despite the weather forecast predicting rain and windy conditions, we were pleasantly surprised by the calm waters and only a few sprinkles during our stay. As the first droplets of rain began to descend, we boarded the water taxi with our gear, including two days’ worth of food, gear totes, firewood, clothing, paddle boards, and a very large toy bag that was bursting at its seams.

The first day we took a walk along the beach, and found common Alaska beach treasures, including shells, rocks of all colors, a skeleton of some sort (possibly bird), and the washed up remains of a jellyfish and starfish. We also encountered an old, rusted car which nature had embraced decades ago. We headed back to the cabin for hot dogs around the campfire to conclude the first day.

The next day we woke to rain kissed leaves and beach rocks. The flat waters were calling our names, and we grabbed our wetsuits and lifejackets and jumped on our inflatable paddle boards for a quick paddle in the cove.

Jellyfish swam beneath us while waterfalls made their appearance along the shores above us. While we encountered a sea lion and otters during our journey, our attempts to engage them were met with indifference, as they maintained their distance, seemingly unimpressed by our efforts. There was the occasional boat and jet ski, but overall, it was very quiet. We made our way to the end of the cove and was greeted with yet another waterfall, and what appeared to be a bald eagle convention. At first they appeared stoic and unbothered, but the longer we stayed the more they made their presence known. Flying overhead and shouting from the treetops. After a snack and an attempt at a family picture (which never captures four smiles at the same time) we placed the boards back in the water and ventured home to the cabin.

We had seen the Porcupine Glacier from the paddle and later in the afternoon decided to take a hike toward it. We followed what appeared to be a trail that followed an old avalanche chute. We had fun ducking and going over trees, yet before long the snow, and post holing, became less fun for the kids. When we sank to our knees in the snow, they sank to their waist. They were happy to turn around and head to the cabin for some playtime. As they played, I snuck away to read a book in the hammock, overlooking the cove.

We ended the trip with more s'mores, card games, creating a fairy house (which any fairy would be jealous of), and family stories on the beach. Another fantastic public use cabin memory stored in the books.

About the Author: Kate Ayers has hiked, biked, skied, canoed, kayaked and water-taxied to more than 40 distinct Alaska Public Use Cabins. She developed her love of the great outdoors at a young age, while growing up in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. Now she aims to introduce her children to the same adventures, beauty, and appreciation for the awe-inspiring Alaskan outdoors.

-

2023

-

Eklutna Lake, Chugach State Park - and the Benefits of Cabin Camping - Matt Dickerson, November, 2023

-

The rain was falling again. Not quite pounding, but more soaking than a mist. Like it had through much of Alaska's summer. I pulled my raincoat hood over my head, hunched over the smoke and flames, warmed my hands momentarily on the heat emanating from the metal fire ring, and proceeded to adjust the PFDs (personal foil dinners) cooking in the coals inside the fire ring. Five of six foil-wrapped packages had expanded nicely, indicating we had successfully folded them accordion style to avoid leaks while still allowing the steam to expand and cook the potatoes, carrots, onions, cabbage, and pieces of steak contained within. Satisfied with the progress of our dinner, I stepped out of the rain and back into the cabin.

"Back into the cabin" was the key phrase. It had been a cool, damp, September day. Early Alaska Autumn. Though the precipitation was still of the liquid variety, the peaks on the far side of Eklutna Lake were gathering their first layer of snow: the "termination dust" that marks the end of summer.

My wife Deborah and I, and our three sons, had met Israel 20 years earlier through a non-profit program called the Fresh Air Fund, which brings kids from New York City out into small towns and rural areas of Vermont (where we live) as well as to upstate New York and Pennsylvania so they can experience the quiet and different pace of non-city life for a week or two. Over the next two decades, Israel had become our "bonus son".

When Israel moved to the Seattle area, I began conspiring how to get him to join me in Alaska and experience not just rural life, but wilderness. Or at least the edge of the wilderness. Someplace like Chugach State Park, where I had spent considerable time over the past 15 years.

The plan finally came together in September of 2023 when Israel, along with his girlfriend Violetta, joined my wife Deborah and me. I had (only half jokingly) promised the two of them an "Alaska experience." We had started the previous day (also a cool, damp, autumnal morning) walking through the city park along Campbell Creek hoping to see a moose. Or maybe a bear. Or some spawning salmon. Any of these would have been part of the Alaska experience.

The plan finally came together in September of 2023 when Israel, along with his girlfriend Violetta, joined my wife Deborah and me. I had (only half jokingly) promised the two of them an "Alaska experience." We had started the previous day (also a cool, damp, autumnal morning) walking through the city park along Campbell Creek hoping to see a moose. Or maybe a bear. Or some spawning salmon. Any of these would have been part of the Alaska experience.

"Are there any mountains around?" Violetta had asked at the start of our walk. "In Seattle, we can always see Mount Rainier. But I don't see any mountains around here."

Deborah and I almost laughed. Had the clouds not been so low and thick, we could have looked in almost any direction and seen peaks rising several thousand feet above sea level. But with all the rain, Violetta and Israel had been in Anchorage for almost 24 hours and not yet seen a single mountain. So much for an Alaska experience. Fortunately, the clouds had lifted by mid-morning, and the mountains lining the eastern edge of the city had revealed themselves in their glory.

But no moose had. Nor any bear. And the creek had been too high and turbid (from all the rain!) to spot any fish. So, since wild animals could not be counted on to appear at our whims, we drove down the Turnagain Arm and spent a couple hours walking around the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center and saw both moose (up close) and brown bear as well as black bear, woodland bison, caribou, deer, musk ox, elk, lynx, and fox. A worthwhile stop.

Next stop was mountains. And wilderness. And camping. The potential for danger and misery, which also seemed important to an Alaska experience.

Except I wanted Israel to come back again, so I didn't want any actual misery. Which is why for our overnight "camping trip" on the boundaries of wilderness I had eschewed tents and instead reserved a cabin at the Eklutna Lake campground in Chugach State Park. The Dolly Varden cabin (which can be rented and reserved through Alaska State Parks) is "primitive" in the sense of having no electricity, no running water, and no mattresses on the wooden bunks. But it is quite spacious. (My thought was that it could easily slept eight in the bunks and several more up in a loft.) It was also dry. And warm (especially after we got the wood stove going). Unlike a tent, it also offered solid wooden walls, meaning we could eat and store our food inside without having to worry about bears. All in all, quite luxurious. A good way to experience the beauty of the place. Did I mention warm and dry?

Which may be why when my nephew Michael, a resident of Anchorage—who had recently returned from a caribou hunt in the Arctic, involving both tents and a long hike with a lot of gear, definitely some risk of danger, and certainly some misery—drove up from Anchorage after work and joined us for the evening, he proclaimed quite definitively, "This isn't camping."

And that was okay with me. Because the truth is, I reserved the cabin as much for myself as for Israel and Violetta. Although Deborah and I both enjoy sleeping in tents—and do so every summer in various state parks—we are also happy at times, especially during shoulder season, and during the sort of constantly rainy summer that has plagued many parts of Alaska, to enjoy the luxury of a state park cabin.

And the stay didn't disappoint. The hike along Eklutna Lake was stunning in its beauty. The lake, despite being flooded well above its usual banks, was remarkable calm, mirroring the distant peaks. Views opened in all directions, with the magnificence being magnified rather than hindered by the clouds and fog clinging to the slopes. On the drive in, we even saw a herd of a dozen wild Dahl's sheep. Somehow we even managed to get in several miles of hiking before the rain started to fall (again). We slept in late in cozy sleeping bags in the comfort of a state park cabin. Drank instant coffee (the closest I came to suffering) and ate instant oatmeal.

And only one of the six foil meals burned. Just enough to make us feel like we were roughing it, but not such much that we didn't want to return.

About the Author: Matthew Dickerson (www.matthewdickerson.net) was an artist-in-residence for Alaska State Parks in 2022. His creative non-fiction writing about Alaska has been published in various journals, magazines, and newspapers as well as in the books 'The Voices of Rivers: Reflections on Places Wild and Almost Wild' (published by Homebound Publications in 2019) and the forthcoming book 'The Salvelinus, the Sockeye, and the Egg-Sucking Leech'. Matthew Dickerson lives in Vermont and teaches at Middlebury College. He is a member of the Outdoor Writers Association of America

-

-

Exploring the Grewingk Glacier Trails and Hand Tram - Kate Ayers, August, 2023

-

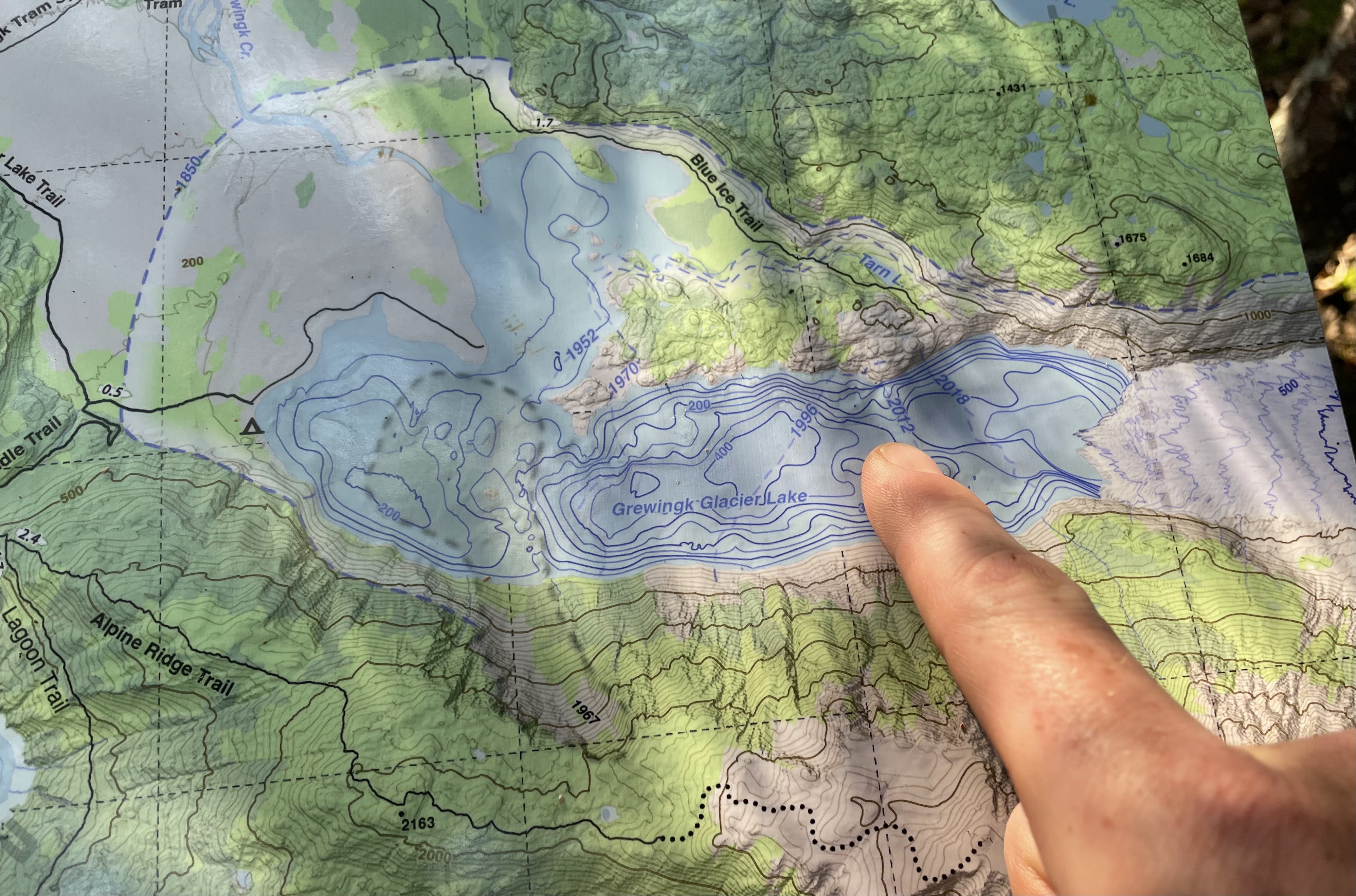

Alaska is an amazing place and I look forward to showing off its glory when we have out of state visitors. Therefore, when we heard our family from Washington and Michigan would be visiting, we booked a trip to Kachemak Bay, near Homer, Alaska. Kachemak Bay State Park became Alaska's first state park in 1970. Kachemak Bay State Park, along with the adjoining Kachemak Bay State Wilderness Park to the south, encompasses nearly 400,000 acres of fun and adventure. Normally, I would have snagged one or two of the six public use cabins (PUC) that Alaska State Parks has made available in Kachemak Bay State Park. However, since we had a large party of ten, and we wanted land access to the Grewingk Glacier Trails, we opted to forgo the PUCs and splurge on local accommodations near the trailhead.

(Photo Courtesy of Katie Petrin)

(Photo Courtesy of Katie Petrin)

The first night, we took our kayaks on a high tide paddle into Halibut Cove. The area is a place of natural beauty, solitude, and diverse wildlife; from bald eagles flying overhead to jellyfish gliding below. As soon as we launched our kayak from the shore, we were startled by a black bear climbing fallen trees in front of us on the beach. As we made our way into the cove, the calm waters were disturbed by a mama Dall's porpoise and her calf playing around us. Their triangular dorsal fin appeared and disappeared in the water as if they were performing a synchronized swimming routine. As we took paddling breaks the hypnotic sounds of a paddle entering and exiting the water was replaced with ad hoc bursts of crunching sounds made by otters nibbling on hard-shelled snacks, or huffs of breath from seals, or from a loud splash of a fish securing an impressive bellyflop as it re-entered into the water after its attempt to reach the clouds.The next morning, our group hiked the Grewingk Glacier Lake Trail. For those doing a day hike, with water taxi pick up and drop offs, it's common to start at the Glacier Spit Trailhead and finish at the Saddle Trailhead. Due to the location of our accommodations, we did an out and back from the Saddle Trailhead side. Starting the hike from the Saddle Trailhead has more elevation gain at the start, but also offers a shorter route to get to the glacier lake. During this kid-friendly trek, we tiptoed around a fair amount of bear and moose scat along the trail. Our hiking breaks were short lived because the pesky mosquitos were always able to find us quicker than we anticipated. Luckily, once we arrived at the glacier the mosquitos were less dense, and the sun and wind kept them away.

The last time I was at Grewingk Glacier was nearly ten years ago. The landscape, to my eye, hadn't changed much over the last decade; however, the amount the glacier had retreated was visually shocking. The trail is sprinkled with informational signs showing the retreat overtime, as well as illustrating the harrowing realization that a rockslide splashing into the lake would likely create a destructive tsunami. In 1967, there was a major avalanche into the lake that created a wall of water over 200 feet high. Today, the slope surrounding the lake is much steeper, which would result in an even higher wall of water.

In the meantime, the area presents a beautiful playground for young and old alike. We spent a few hours at the lake throwing rocks, breaking ice, polar plunging, and paddle boarding around icebergs. We headed back down the trail late afternoon. Near the end of the hike, I heard a loud and irritated huff coming from dense vegetation just beyond the trail. The next day, a group of hikers saw a sow and three cubs in the same spot - be bear aware.

Although the glacier lake was amazing, my husband and I still wanted to check out the hand tram over Grewingk Creek, which leads to the less popular Blue Ice and Emerald Lake Loop Trails, both on the north side of the Grewingk Glacier. Our family was kind enough to take our kiddos for the morning while we kayaked to the Glacier Spit Trailhead. We pulled our kayaks up on the shore and then started on the popular trail, spotted with cottonwood and Sitka spruce overhead. Not long after we started, we came to an intersection. Hikers wanting to go to the glacier stay straight, we took a left turn and headed to the hand tram.

The hand-operated cable car pulley system, or hand tram, is best operated by at least two people. Ideally, one person crosses at a time, so the other person can stay behind and assist in pulling the other across from the land platform. There is a maximum weight of about 500 pounds, so ensure you know the weight of you and your belongings. It is also recommended to bring your own gloves. I was beyond excited that there was an open bag of work gloves available for use at the base of the tram, these came in very 'handy' since I had accidentally left my gloves in the cabin. As you cross Grewingk Creek it becomes hard to hear anything besides the raging river below your feet, it's a thrilling experience. We explored the creek and surrounding areas then headed back to the family.

I sure hope I don't wait nearly another decade to visit this amazing spot.

About the Author: Kate Ayers has hiked, biked, skied, canoed, kayaked and water-taxied to more than 40 distinct Alaska Public Use Cabins. She developed her love of the great outdoors at a young age, while growing up in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. Now she aims to introduce her children to the same adventures, beauty, and appreciation for the awe-inspiring Alaskan outdoors.

-

-

Of Rain, Glaciers, Salt Chucks and Silver Salmon: An Alaskan Arts Residency - Matthew Dickerson, July, 2023

-

Note: Writer Matthew Dickerson and visual artist McKenna Dickerson were collaborative artists-in-residence for Alaska State Parks in September of 2022. Matthew (www.matthewdickerson.net) is a professor at Middlebury College in Vermont and the author of several books of narrative non-fiction including The Voices of Rivers: Reflections of Places Wild and Almost Wild (much of which was set in Alaska including in Chugach State Park) and The Salvelinus, the Sockeye, and the Egg-Sucking Leech which is about rivers, native fish, and ecology in Bristol Bay, and was completed during his artist residency in Wood-Tikchik State Park. He also contributes regularly to American Fly Fishing and one of his articles on fishing on Peterson and Cowee Creeks near Ernest Gruening State Historic Park and Point Bridget State Park appeared in the May-June issue of Amerian Fly Fishing. He is a member of the Outdoor Writers Association of America and writes a regular outdoors column for The Addison County Independent in Vermont. The following is revised from two columns appearing in that paper in September 2022.

On mid-September day in 2022, I sat near my daughter-in-law McKenna and her sister Sophie on the second-floor balcony alcove of Resurrect Art, a wonderful little cafe in Seward Alaska a few miles from the trailhead to Caines Head State Recreation Area. McKenna—who works as a Youth Art Instructor for Davis Studio (in South Burlington, Vermont) while also continuing her own art practice—had graduated a year earlier from Saint Michael's College in Vermont where she studied fine arts and environmental studies. She and I had been selected for a collaborate arts residency for Alaska State Parks. Our residency in two Juneau area state parks had just ended. (You can see some of McKenna work including paintings inspired by Juneau area state parks at her website: www.mckennadickerson.com/)

I would soon be traveling to Port Alsworth in the middle of Lake Clark National Park to teach creative writing at the Tanalian School for a few days and then to spend a few days at The Farm Lodge (my favorite location in all of Alaska for a fishing and wildlife-viewing adventure) while McKenna was getting ready to head back to Vermont. This was our last day together in Alaska. We had planned to visit Caines Head State Recreation Area and hike down to Tonsina Creek to see the beautiful views from there—an excursion I had enjoyed back in July with other family members. But it was pouring in Seward with rain predicted to continue for the next forty-eight hours accumulating up to five inches. The National Weather Service has issued a warning about possible stream flooding. The famous glaciers and the mountaintops surrounding us were invisible. Even the bases of the mountains surrounding Resurrection Bay were just faint shadows in the gray. Having experienced plenty of rain over the previous week and a half, I was not even tempted to go outside and look for sea otters or seals. So instead, we sat at Resurrect Art enjoying a mocha and a delicious lemon lavender scone and staying dry. Not a bad consolation. Also a good opportunity to start turning pages of notes about our stay at two state parks into some sort of coherent narrative.

One of those parks—the one where we spent the majority of our time—was Ernest Gruening State Historic Park where we stayed at Eaglerock cabin. The cabin was built for Ernest and Dorothy Gruening, the former of whom served as a governor of the territory of Alaska and then as senator of the state of Alaska after playing a significant role in the territory becoming the 49th state. The cabin sits on the coast with a deck looking over Amalga Bay and beyond to Lynn Canal and the distant peaks of Glacier Bay National Park and Tongass National Park.

The cabin's name was not a misnomer. Numerous bald eagles were, indeed, around the cabin almost constantly, often sitting on rocks right below—though they also made use of the tall hemlocks atop the bluffs. Guests of the Gruenings at the same cabin where we stayed included Earl Warren, Adlai Stevenson, and John F. Kennedy (when he was a senator). It was at the cabin that Gruening wrote many of the magazine articles as well as the book The State of Alaska that helped lead to the territory becoming the 49th state (for which Gruening then served as senator for two terms.)

The cabin's name was not a misnomer. Numerous bald eagles were, indeed, around the cabin almost constantly, often sitting on rocks right below—though they also made use of the tall hemlocks atop the bluffs. Guests of the Gruenings at the same cabin where we stayed included Earl Warren, Adlai Stevenson, and John F. Kennedy (when he was a senator). It was at the cabin that Gruening wrote many of the magazine articles as well as the book The State of Alaska that helped lead to the territory becoming the 49th state (for which Gruening then served as senator for two terms.)

The history of the place was inspiring and I soaked in as much as I could. Yet it was the surrounding scenery and landscape that moved me the most. Looking out the front deck of the cabin across Lynn Canal we could see in the distance the 4000-foot snow-capped peaks of Tongass National Forest and Glacier Bay National Park. Behind us on the same shore rose the 6000-foot peaks of the Juneau Ice Field and its numerous glacier arms: Herbert, Eagle, and the more famous Mendenhall Glaciers.

Closer in front of us was the calm water of Amalga Bay. During our stay, we had regular visits from a seal, a passing raft of otters, and more bald eagles than we could count. We even had a brief sighting of a humpback whale and a longer sighting of a pair of minke whales. (We also had several sightings at low tide of large rocks out in the bay pretending to be whales and eliciting at least one excited cry of "whale".) A sea lion also passed by one day when I was inside writing, but I missed it. I could see why Gruening fell in love with the place and could be so inspired to argue for Alaska's statehood.

But if it had been me arguing for statehood, I might have devoted even more words to the "salt chuck" lagoon on other side of the cabin (and not only because I had never heard of a "salt chuck" before), and to the Peterson Creek flowing into it. Because that was not only where I saw the tundra swans and the family of river otters, but also where I caught a lot of silver salmon, coastal cutthroat trout, and sea-run Dolly Varden char.

So what exactly is a Salt Chuck? That was one of the questions I had when McKenna and I arrived at Eaglerock for ten days as the Rie Muñoz and Dorothy Gruening Artists-in-Residence. On the other side of the cabin from the bay is a serene pond known as the Peterson Salt Chuck, which spills through a narrow gap in the trees over a waterfall down into the saltwater. Or, rather, it usually spills over a waterfall, the height of which depends on the height of the tide. Sometimes, however, the water flows in the other direction.

Before reading the name "Peterson Salt Chuck", I had seen that pond described as a lagoon: a small body of water separated from saltwater by a shallow gravel bar so that the pond and the sea are connected only at high tides. That is, a lagoon is both connected to and separated from the saltwater depending on the tide. A river lagoon, as the name suggests, is a lagoon fed by a freshwater river; thus the saltwater and freshwater mix forming an estuary. Estuaries are particularly rich in nutrients, and are unique and vibrant ecosystems where saltwater and freshwater meet. The Peterson Salt Chuck is a unique river lagoon in that saltwater can only flow in at very high tides, perhaps a couple times a month. Over the course of our stay, we never had a tide high enough to reverse the direction of the waterfall and allow saltwater to flow into the chuck (unless we missed one in the middle of the night.) The result of this unique geologic configuration is a pond that is layered like a parfait. The bottom layer of the pond is saltwater, and contains some of the creatures you might find in a tidal pool. But the constant inflow of Peterson Creek contrasted with the much rarer influx of saltwater leaves a layer of freshwater atop the pond, making it very welcoming to species like cutthroat trout and trumpeter swans. Illustrating that interesting mix, one day I saw a family of river otters swimming down Peterson Creek toward the salt chuck from above, and another day I saw a raft of sea otters swimming through the saltwater in front of the cabin toward the bottom end of the waterfall.

I also caught Dolly Varden Char, coastal cutthroat trout, and silver salmon in the salt chuck. Most cutthroat and Dollies spend their whole lives in freshwater, but both species are capable of adapting to saltwater life and can move back and forth between saltwater and fresh. Dollies are especially prone to this diadromous life history, and the members of their species that do this are called "coastal Dolly Varden" or "sea-run Dolly Varden"; they have a much more silvery sheen than their purely freshwater relatives . Both cutthroat and Dollies in the Salt Chuck benefit from the nutrient rich estuarial waters. Though both McKenna and I caught a few dollies, the cutthroat fishing proved especially enjoyable and productive. When we took breaks from our artistic endeavors—which for Mckenna was primarily landscape painting in acrylics and for me was creative non-fiction nature, environmental, and outdoor writing—and wandered out to the lower end of the chuck or made our way to the upper end of the tidal water on Peterson Creek above the chuck, we had very good action fly fishing for the cutthroat, catching them on both dry flies and streamers.

I also caught Dolly Varden Char, coastal cutthroat trout, and silver salmon in the salt chuck. Most cutthroat and Dollies spend their whole lives in freshwater, but both species are capable of adapting to saltwater life and can move back and forth between saltwater and fresh. Dollies are especially prone to this diadromous life history, and the members of their species that do this are called "coastal Dolly Varden" or "sea-run Dolly Varden"; they have a much more silvery sheen than their purely freshwater relatives . Both cutthroat and Dollies in the Salt Chuck benefit from the nutrient rich estuarial waters. Though both McKenna and I caught a few dollies, the cutthroat fishing proved especially enjoyable and productive. When we took breaks from our artistic endeavors—which for Mckenna was primarily landscape painting in acrylics and for me was creative non-fiction nature, environmental, and outdoor writing—and wandered out to the lower end of the chuck or made our way to the upper end of the tidal water on Peterson Creek above the chuck, we had very good action fly fishing for the cutthroat, catching them on both dry flies and streamers.

For most local anglers, however, silver salmon were the main attraction there. Most of the day we could see anglers casting for silvers at the inlet to the chuck, and sometimes at the outlet hoping to catch them at the narrow gap as they worked up the falls from the ocean. Some cast directly into saltwater from shore, and one day an angler came across the bay on a standup paddleboard to cast flies into the outlet of the waterfalls. (I didn’t see him land one, but a large silver did grab his fly and manage to break his line.)

Though I only targeted silver salmon with my salmon fly rod once, I still managed to catch several silvers while casting for trout with my lighter-weight fly rod. They were smaller silvers—only a little bigger than the cutthroat trout I was catching, and not likely to break my line—but were still fun to catch. So I was surprised one morning when I walked out to the chuck at sunrise to take photos of the wildlife and the sun rising over the snow-covered peaks to the east, and found the chuck devoid of anglers. I soon learned that the state had closed the water to salmon fishing due to low numbers of returning salmon. Given the decline of many species of salmon in many waters of the north Pacific, I was curious (and concerned) about the reasons, and interested in following up on the story. [See the note below.] The shortage of returning silver salmon was likely the reason we didn’t see many seals or sea lions feeding around the mouth of the Peterson Salt Chuck.

But in the meanwhile, I was content to keep writing while McKenna painted, to keep an eye (and a camera lens) on the ocean for passing whales, seals, sea lions, eagles, and sea otters, and to keep gazing at the Salt Chuck for glimpses of river otters, trumpeter swans, and reflections of snow-covered peaks. And occasionally to toss flies into the darker estuarial waters in hopes of getting the attention of the resident trout.

Hiking trails along the bluff over the ocean and good views of the Salt Chuck, along with the historical significance of the cabin, make the park a beautiful place to visit. I hope I can return some day. And whether I return or not, I hope the silver salmon come back.

Addendum: After the residency, I was able to contact ADFG fisheries biologists Dan Teske and Dave Love and had a very enjoyable and informative conversation with them about both the excellent fisheries on many Juneau area rivers (including Peterson Creek), and also the decline in silver salmon on Peterson Creek. Some of that decline might be attributed to increased fishing pressure. A 2020 avalanche damaged a fish hatchery in Juneau wiping out 80% of the hatchery fish which supported some of the rivers close to town. Although Peterson Creek silver salmon are wild (not hatchery fish), more anglers moved north from Juneau due to the loss of hatchery fish. The bigger impact, however, has been a decrease in marine survival of silver salmon due to environmental reasons. Silver salmon fishing is therefore likely to be closed or poor in Peterson Creek in the near future. ADFG will be keeping a close watch, and they have many decades of data to use in their decisions. Thankfully, the cutthroat fishing is still excellent on Peterson and there are other good rivers in the Juneau area for silver salmon fishing including Cowee Creek which flows along the east side of Point Bridget State Park, within walking distance of the state park cabin on Cowee Meadow. But that is another story.

-

-

Disabilities are everywhere; some invisible and some not - Helen Michaelson, June, 2023

-

Living with a physical disability, but loving outdoor adventures is certainly not the most ideal combination; but for me it is a necessity for my physical as well as mental health! Accessibility and inclusiveness are constantly growing themes in today's world; maybe not fast enough, but growth nevertheless.

Living with a physical disability, but loving outdoor adventures is certainly not the most ideal combination; but for me it is a necessity for my physical as well as mental health! Accessibility and inclusiveness are constantly growing themes in today's world; maybe not fast enough, but growth nevertheless.

My favorite place to bike, swim, kayak, run and hike in the Mat-Su Valley is Matanuska Lake Recreational Area which touches the Mat-Su Green Belt and Experimental Farm. There are many trails that connect all these places. My Great Grandpa, Grandpa and Uncle all worked at the Experimental Farm, so there is always an extra sweet connection to these trails for me.

The view of Pioneer Peak and Matanuska Lake on one side, Lazy Mountain and Matanuska Peak on one, the flats leading towards the inlet and Hatcher Pass on the other is unreal; it seems like I can never get enough of them. This place for me holds many memories and miles for me; from high school cross country running practice, time spent hiking with my best friend, mountain biking, long runs, lake days with my family and so much more in between. As I get older, I crave more time alone to process and reflect on life; and this spot is my all-time favorite place to do so.

Living in the Mat-Su; we have so many options that are conducive to different abilities! Winter, Spring, Fall or Summer; getting out in the wonderful array of state parks to exercise is good for mind, body and soul for everyone regardless of your abilities! I hope to see all abilities out on the trails and strive to advocate for an increase of access for all.

-

-

K'esugi Ken: Denali Public Use Cabin - Kate Ayers,

May, 2023

-

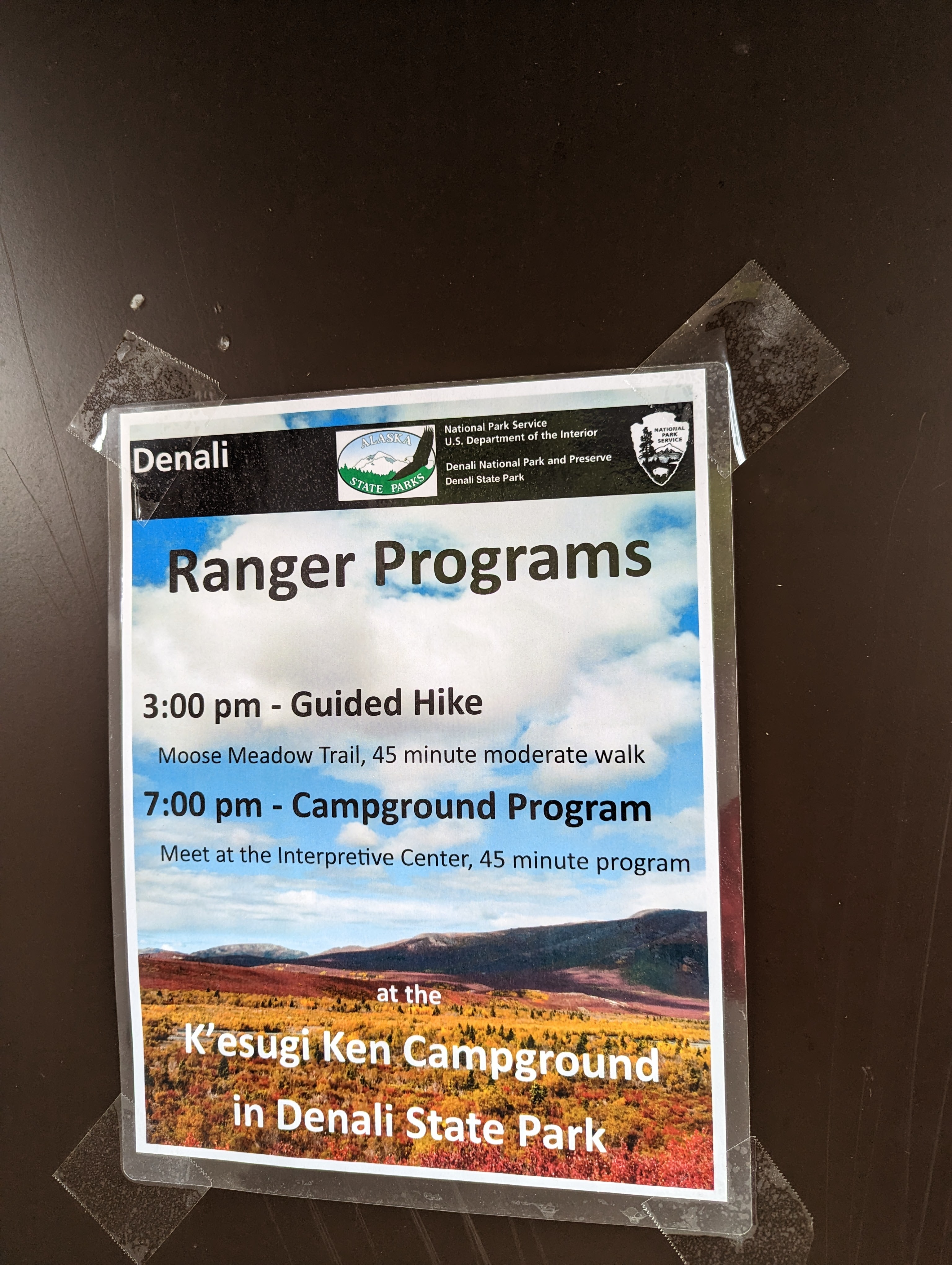

In late-May, our family of four headed north from Anchorage to the Denali Public Use Cabin (PUC) within the K'esugi Ken Campground, located in Denali State Park. This was our family's second time staying in one of the three awesome K'esugi Ken cabins, and our first time without snow on the ground.

The Denali cabin is a drive-up cabin, built to ADA standards, and is the one of the largest PUCs I've stayed in. It includes a woodstove, loft that is accessible by a spiral staircase, a downstairs bedroom, and electricity – yes lights! The back door opens out to a good-sized porch that has a peek-a-boo view through the trees of the Alaska Range on clear days. This spacious and well-lit PUC was originally only available to rent during the winter and occupied by a campground host during the summer. However, in recent years the cabin has been open to rent in the summer while the campground host RV parking spot is directly next to the cabin (roughly 10 feet). Therefore, if you're looking for seclusion in the summer, you may want to find another PUC.

Once we arrived, and after the kids played a few rounds of hide-and-seek, we ventured out to the West Hoodoos Trail, just feet from the back door. As you follow the beautiful views of the Alaska Range, the trail brings you to the Moose Flats Loop Trail. The Moose Flats Loop Trail is just over half a mile long and is wheelchair accessible. It leads you to a few small ponds and over a wooden bridge. Watch out for wildlife, including the local ducks and frogs. There is a viewpoint near some large rocks which provides an amazing view of Mt. Denali on a clear day. Unfortunately, we didn't have any luck seeing the Great One during this trip, but still remember the view from the last time we were there with clear skies. We finished the loop walk right before the raindrops fell from the sky. That night we munched on s'mores, played more hide-in-seek and finished a puzzle.

The next morning, we filled our day pack with snacks and water, and headed out to the Curry Ridge Trail. Given it was our first family hike of the season, we didn't know how far we'd get. Since I was not interested in carrying our four-year-old, my goal was to hike two miles out of the 6.5-mile out-and-back trail, with a 1,100-foot assent.

The cloud coverage kept us cool as we hiked up the wide meandering path. There were hardly any bugs, and the birds were serenading us along the way. Jumping on each large rock found in, or near, the trail was the motivating factor for our children to keep going. The rocks became their on-land surfboards and after they were done riding the dirt wave, they would get off to catch the next one along the path. After about a half mile on the well-maintained gravel trail, we reached a small footbridge with a creek underneath. Beyond the bridge, the trail remained in good condition with just a few muddy spots and small water crossings, mostly from trickling snow melt from above. Our pace was slow and exploratory, yet we kept moving in the right direction – up. Although the clouds covered Denali, the trail still offered great views of the lower Alaska Range. After we were above the tree line it became cool, and our bellies started grumbling. We found a large rock to take a break before we headed back down. As the kids and I munched on our trail mix, my husband took the trail a little further up and reached the loop signs within two minutes.

As we headed back down, the kids entertained us by selecting sticks and using them as band instruments. We later passed a few hikers that mistook the unique trumpet and flute sounds as an odd moose call. As the parking lot came into view, the rain started, or as my four-year old would say, "the clouds released their full bellies." Not sure how we made it to the top, or how we missed the rain during the hike, but I was impressed with the trail, the view, and the overall experience.

Heading to K'esugi Ken soon? Here are a few things to keep in mind:

- Late May was the perfect time for us, as the swarms of mosquitos were not out yet. I have heard horror stories of people being chased all the way back to Anchorage in prior years given the amount of uninvited mosquitos that joined them.

- Ironically, the K'esugi Ken Ridge Trail does not start from the K'esugi Ken Campground.

- The campground has a large Interpretive Center that contains information about Denali State Park and the Alaska Range. There are hikes and other interpretive programs provided most summer days. We found the Ranger Programs schedule on the bathroom door.

- There was a little library (take one, leave one) at the campground pay area.

- Fiddleheads, fiddleheads, fiddleheads! We enjoyed harvesting and cooking them as a side for our dinner.

About the Author: Kate Ayers has hiked, biked, skied, canoed, kayaked and water-taxied to more than 40 distinct Alaska Public Use Cabins. She developed her love of the great outdoors at a young age, while growing up in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. Now she aims to introduce her children to the same adventures, beauty, and appreciation for the awe-inspiring Alaskan outdoors.

-

-

Ernest Gruening State Park - Matthew Dickerson, September, 2022.

-

Morning. Peterson Salt Chuck.

Morning. Peterson Salt Chuck.

The morning air is thick and brooding. The world feels muted. Reflected on the still surface of the Peterson Salt Chuck, spruce trees blur together, and clouds appear more green than gray. On the far shore, above the water, a waiting world unfolds in layers of hues: the softer yellow-green of shoreline grasses giving way to the darker spruce whose spires point skyward toward the taller and more distant peaks of Mount Ernest Gruening where last winter's snow still clings to gray slopes beneath a heavy slate sky.

A pair of trumpeter swans rest in the stillness at the far side of the estuary, icons of grace and elegance, as solemn and majestic as the peaks behind them. At the first hint of disturbance in their throne room, they turn and disappear behind the grasses into their private chambers. A lone bald eagle remains behind, on guard, looking down on the Peterson Salt Chuck from atop a tall spruce near the falls where the brackish water pours down into the ocean.

Below the surface, invisible to the eagle's sharp eyes, silver salmon swim slowly across the chuck—a final journey that brings them from ocean brine up into the cool freshwater where their eggs will soon fall on river-bottom gravel. Sea-run Dolly Varden char with silvery green sides follow the salmon upstream to feast on any eggs that drift free.

I am raptured by the holiness of the moment, of the place, the sanctuary in which I now stand. Speech seems sacrilege. A family of river otters swims down Peterson Creek. Constantly diving and darting around and beneath one another, they are impossible to count. I give up trying, and simply delight in their presence. Even their play is holy. A sacred dance.

Afternoon. Amalga Harbor.

The heavy blanket of gray has lifted. The brooding ceiling has turned to a cheerful blue picnic ground where clouds, white and weightless, swim and dance across the sky like playful otters. The shoreline trees are brighter now. Their tops crisp and sharp against the azure backdrop as they soak in the midday light.

The tide is out. The waters of Peterson Creek have their last chance to play as they tumble down from the Salt Chuck and into Amalga Bay where they are swallowed up in the ocean's vastness, as blue and wide as the sky above. Gulls the color of the clouds hop on the rocks plucking food scraps out of the seaweed left behind by the receding tide. Some take to wing where they bob and flutter in the breeze while scanning the brine below for their next meal.

The bald eagle still waits on his tree, guarding the flowing path from ocean to lagoon, lagoon to ocean. A harbor seal patrols the water below, also waiting for another school of silver salmon as they start their final journey, ascending the falls, crossing the salt chuck, and swimming up Peterson Creek to some secret spot where male and female will pair up for the one and only time in their lives—to spawn and then to die, ending one generation, and starting another.

A raft of sea otters visits, bobbing and rolling like their smaller river otter cousins. The passing mergansers bob too, but in more orderly lines. A lone raven, black and yet as bright and shiny as the gulls, watches the drama from its perch nestled in the branches of a shoreline spruce.

Evening. Lynn Canal from Eagle Rock Cabin.

The water is pale blue in the late afternoon light, swirled in elusive patterns of wind and scattered rain. Out in the offing near the edge of Amalga Bay not far from where ferries and cruise ships pass up Lynn Canal, a pair of humpback whales breach. Their spouts reveal their presence to any fortunate passers-by watching from shore. Two magnificent pairs of flukes rise high in the air, one after another, and slip away.

Quiet returns. Wooded islands appear dark and mysterious. At low tide, rocks rise above the water far from shore, like passing humpbacks that never pass. Never spout. Never lift their flukes. Excited exclamations of "whale!" fade to embarrassed mumbles of "never mind."

Quiet returns. Wooded islands appear dark and mysterious. At low tide, rocks rise above the water far from shore, like passing humpbacks that never pass. Never spout. Never lift their flukes. Excited exclamations of "whale!" fade to embarrassed mumbles of "never mind."

When fog grows thick or rain rolls in hard and steady, the majestic heights on the far shore disappear behind the curtain. At those times, one might believe this water a mere canal as its name proclaims, and not one of the deepest and longest fjords in the continent. Today that does not happen. Although a cloud dome has once again spread across the sky above, the long row of mountains rising thousands of feet above sea level are still visible across the water. My eyes are drawn there now, to the heights and slopes of the Chilkat Range that divide Glacier Bay National Park and Tongass National Forest—iconic snow-capped peaks and white-splotched mountainsides guarding glaciers and deeper snowpacks in the valleys between. I look at the heights but only imagine the depths, carved by the slow and patient weight of time and glacier, directed by the invisible hand of the Great Sculptor.

The view from Ernest Gruening State Historic Park is magnificent. It can leave one wordless. Even breathless. Or, rather, full of breath. At once both sated and longing.About the Author: Matthew Dickerson (www.matthewdickerson.net) was an artist-in-residence for Alaska State Parks in 2022. His creative non-fiction writing about Alaska has been published in various journals, magazines, and newspapers as well as in the books 'The Voices of Rivers: Reflections on Places Wild and Almost Wild' (published by Homebound Publications in 2019) and the forthcoming book 'The Salvelinus, the Sockeye, and the Egg-Sucking Leech'. Matthew Dickerson lives in Vermont and teaches at Middlebury College. He is a member of the Outdoor Writers Association of America

-

2022

-

The Gift of Adventure - Kate Ayers

-

We all know that Alaska State Park Public Use Cabins (PUC) are a hot commodity these days. Therefore, what better holiday gift to give than a night or two at an Alaska State Park PUC? There is a cabin out there for everyone, who is on your list?

We all know that Alaska State Park Public Use Cabins (PUC) are a hot commodity these days. Therefore, what better holiday gift to give than a night or two at an Alaska State Park PUC? There is a cabin out there for everyone, who is on your list?

Drive-Up Explorer

These cabins are for people who want to load the car, have a short drive, and unload gear at the front step of a cozy cabin. These cabins are perfect for families with little ones, or those that have mobility constraints.

- Bore Tide Cabin (Chugach State Park)

- Birch Lake Cabin (Northern Region)

- Rhein Lake Cabin (Nancy Lake State Recreation Area)

Adventure-Lite

Adventure-Lite

These cabins are for people who want to get away from the crowds, but at the same time can get back to the car quickly if needed. If you're just getting into backpacking and want to do a 'test run' these cabins may be for you.

- Tonsina Cabin (Caines Head State Recreation Area)

- Byers Lake Cabin #2 (Denali State Park)

- Nancy Lake Cabin #2 (Nancy Lake State Recreation Area)

Experienced Outdoorsperson

These cabins are for people who are experienced in outdoor adventures and choose to explore beyond the most populated adventure spots. These cabins may require additional planning, such as water taxis, or a kayak or canoe rental.

These cabins are for people who are experienced in outdoor adventures and choose to explore beyond the most populated adventure spots. These cabins may require additional planning, such as water taxis, or a kayak or canoe rental.

- Kokanee Cabin (Chugach State Park)

- China Poot Lake (Kachemak Bay State Park)

- Red Shirt Lake Cabins (Nancy Lake State Recreation Area)

Now is the time to book the adventure for your friends and family. The Alaska State Parks PUCs reservations system open 7 months prior to the booking date. Popular cabins often get snagged at 12:01 am exactly 7 months out. Plan ahead this holiday and give the gift the adventure at an Alaska State Parks PUC.About the Author: Kate Ayers has hiked, biked, skied, canoed, kayaked and water-taxied to more than 40 distinct Alaska Public Use Cabins. She developed her love of the great outdoors at a young age, while growing up in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. Now she aims to introduce her children to the same adventures, beauty, and appreciation for the awe-inspiring Alaskan outdoors.

-

-

Caines Head Rainforest Loop - Kate Ayers

-

I was excited, and surprised, that I was able to snag the Callisto Public Use Cabin in the Caines Head State Recreation Area, without booking it six months ahead of time. I quickly realized why it was available. The only access to the cabin would be by water because the low tides were still not low enough to take the beach trail to the cabin. With this knowledge, we decided to get dropped off by a water taxi and bring a tandem kayak along for adventuring. As we drove down to Seward, the forecast showed 90% rain for the next five day, and it wasn't wrong. We arrived at the cabin the first night, got the fire started and got warm food in our bellies.

I was excited, and surprised, that I was able to snag the Callisto Public Use Cabin in the Caines Head State Recreation Area, without booking it six months ahead of time. I quickly realized why it was available. The only access to the cabin would be by water because the low tides were still not low enough to take the beach trail to the cabin. With this knowledge, we decided to get dropped off by a water taxi and bring a tandem kayak along for adventuring. As we drove down to Seward, the forecast showed 90% rain for the next five day, and it wasn't wrong. We arrived at the cabin the first night, got the fire started and got warm food in our bellies.

The next morning, the reddish-orange lion's mane jellyfish joined us as we kayaked along to North Beach to start our hiking adventure from the Fort Trail. The trail to the top of Caines Head, and to Fort McGilvray, is beautiful. We welcomed the trees that towered above our heads, as they caught a large amount of the continuous raindrops before they reached our brightly colored soaked hoods. The landscape along the trail proved that rain was not an unusual occurrence in the area. We walked through bright green moss and small streams braided throughout the trail. As the trail approached the Fort, it became peppered with World War II remnants; a bunker tucked into the woods here, and a twisted sheet of metal there. After a 650-foot climb and about two miles of hiking, we reached Fort McGilvray. This once lively strategic command center is now dark, cold, and eerie. Even with flashlights and a lantern I still didn't have the gumption to explore the dark corners. Following the small amount of natural light out to the other side, we were met looking down at a large circular platform. This moss-covered aged concrete was the location of the firing platforms that stood ready nearly 80 years ago protecting the Port of Seward.

From the platforms, the path brings you back to the fork in the trail where the decision to head North or South is made. Heading North will lead you back to North Beach where the trail starts. If South is chosen, the path descends through the trees to South Beach. As we made our way down to South Beach it was fun to imagine 500 military personnel making this landscape their home. How many rocks did they skip into the ocean, or how many naps did they take on the beach? Although I wasn't able to take a nap on this adventure, I tallied at least three skipping rocks. After the 1.5 miles of hiking down to South Beach the majority of visitors turn around and make their way right back up the hill and on to North Beach the way they came; what they may not know is that they're missing a wonderful loop trail that brings them into the woods to experience the rainforest, waterfalls, and plump blueberries.

These days it's hard to find a trail in Alaska that is not widely popular, but I'm here to say – they do exist! If you research "Rainforest Loop Trail" you won't find much. The last time I completed the Rainforest Loop Trail we hardly found the trailhead, we lost our way several times, and the trail was nearly being washed away from the elements. In fact, the only group of people that we encountered on the trail that day told us that they had heard of the loop trail, but they didn't want to get lost in the woods, something I could vaguely relate to from my prior experience. However, this time I was pleasantly surprised to see what appeared to be a brand-new sign, equipped with destination mileage, greeting us at the trailhead. The new sign set the stage to the rugged, yet surprisingly well-maintained trail. This time, the key to not getting lost was simple: follow the pink tape. Follow the tape through the trees, along waterfalls and through the running creek beds. The scenery is so beautiful that we were looking up, down, and all around throughout the entire trail so we were unlikely to miss the pink tape. At mile 1.7 we encountered what is likely an even less popular trail – the Alpine Trail. I've always wanted to explore this one but was given the advice to avoid the trail on a socked in day, as views would not be visible. Given I felt like I could reach out and touch the clouds hovering directly over our heads, we opted out of traversing the Alpine Trail. With the majority of the water features behind us, the last section of the loop down was quick. After another 1.4 miles we came to the Overland Trail intersection. Those staying at the Derby Cove cabin, or walking along the beach from Seward, would have taken this left. However, since we beached our kayak at the other trailhead, we took a right and made a quick 0.6 mile jaunt over to North Beach.

Although the raindrops on our coats had grown their own raindrops when we finished, we still had a terrific time. We had the entire Rainforest Loop Trail to ourselves, besides the unseen goat that was that was leaving its fresh tracks in the mud just ahead of us.About the Author: Kate Ayers has hiked, biked, skied, canoed, kayaked and water-taxied to more than 40 distinct Alaska Public Use Cabins. She developed her love of the great outdoors at a young age, while growing up in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. Now she aims to introduce her children to the same adventures, beauty, and appreciation for the awe-inspiring Alaskan outdoors.

-

-

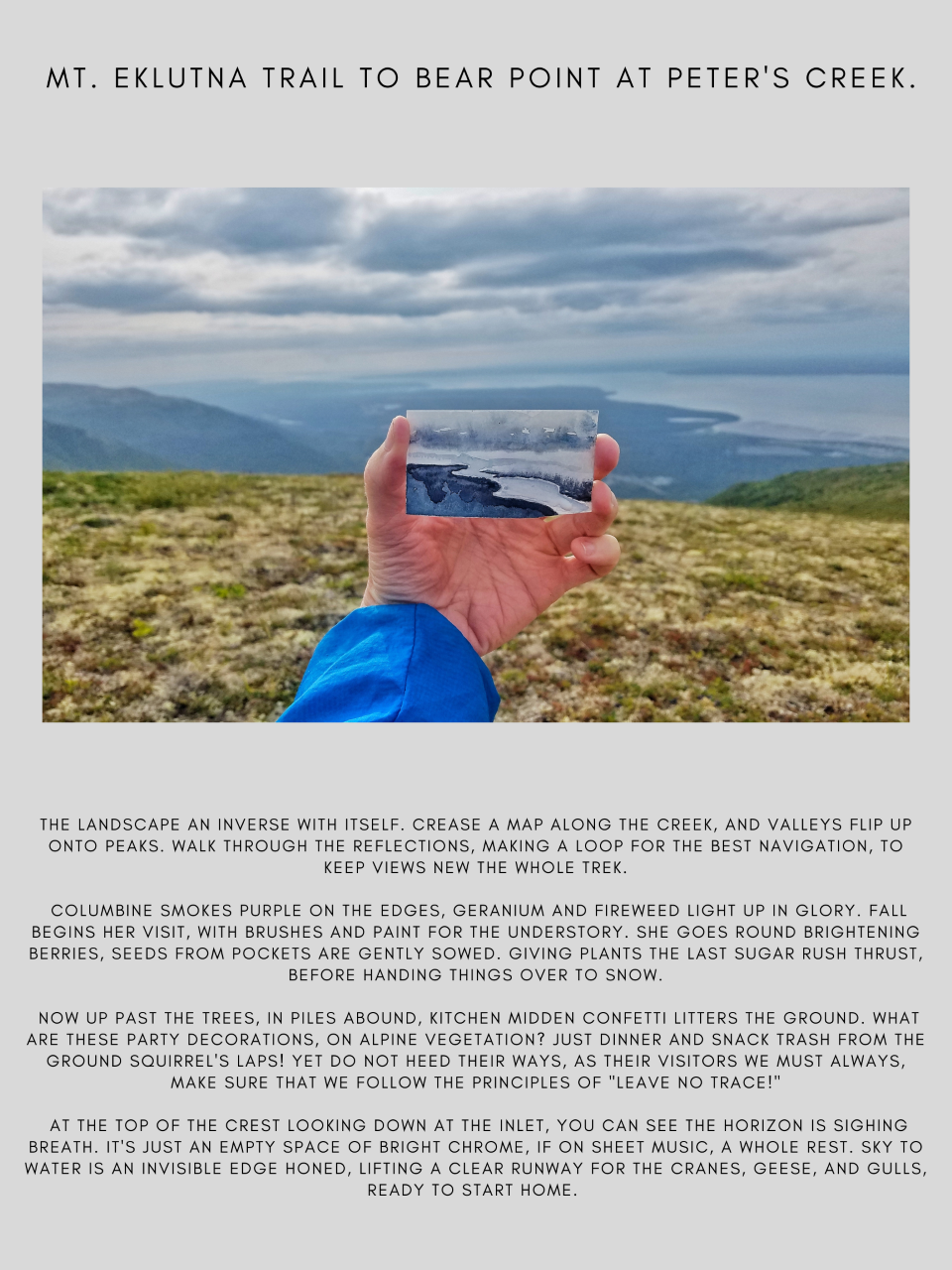

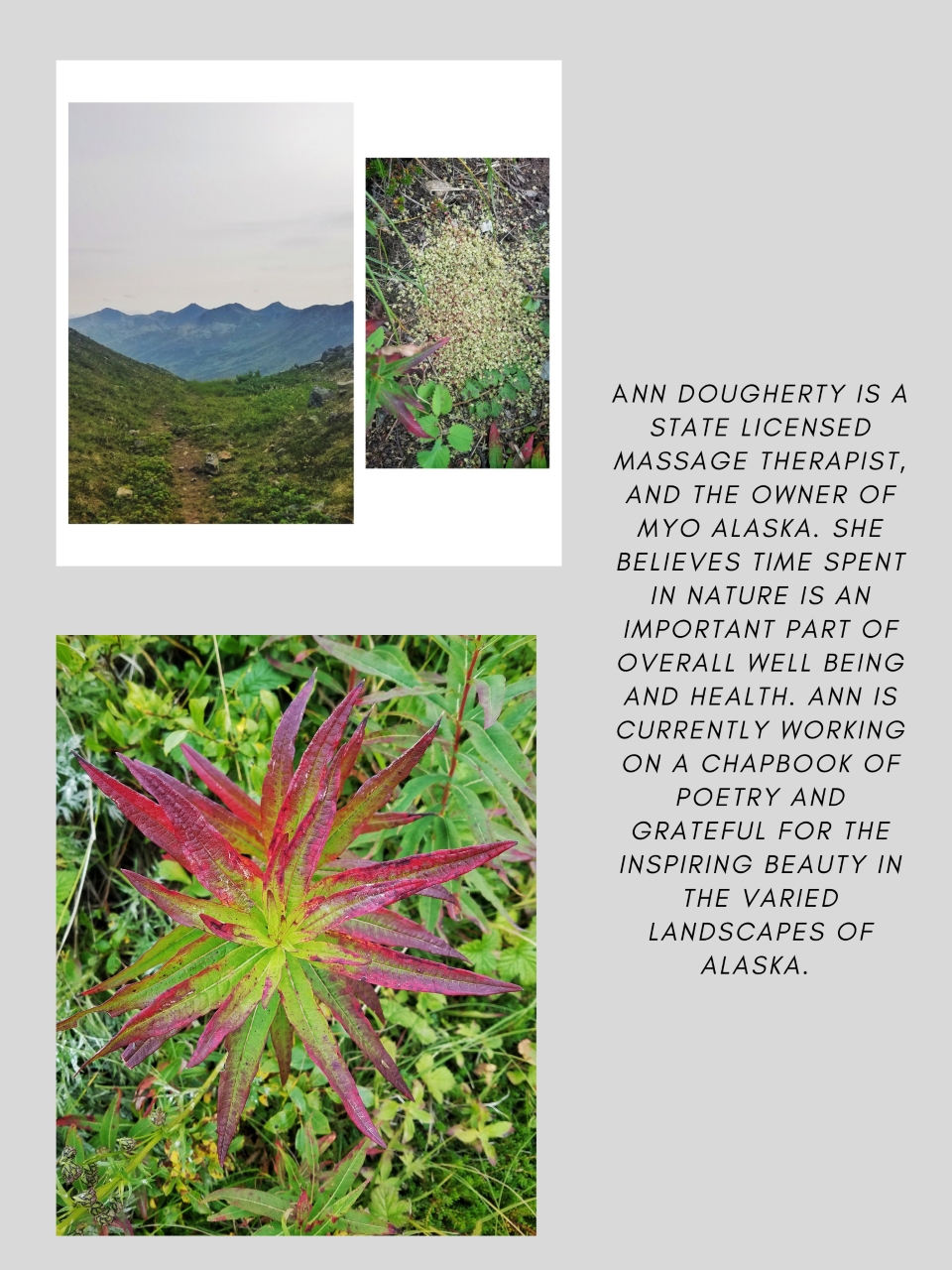

Mt. Eklutna trail to Bear Point at Peter's Creek - Ann Dougherty

-

Tonsina Cabin - Kate Ayers

-

Mini-backpacker - start them young

Our latest cabin adventure was a milestone for our family – our oldest (5 years old) was able to backpack not only her toys, but also her clothes and water the two miles into the Tonsina Public Use Cabin. The trail goes through maritime rainforest featuring vibrant green trees towering above, bridges that cross over salmon streams and ends at the picturesque Tonsina Point in Resurrection Bay. The landscape variety kept her, and the entire family, entertained throughout the hike. We won’t expect her to backpack in ten miles anytime soon, but it does start to shift our thinking into what is to come in the next stages of our adventures in just a few short years.

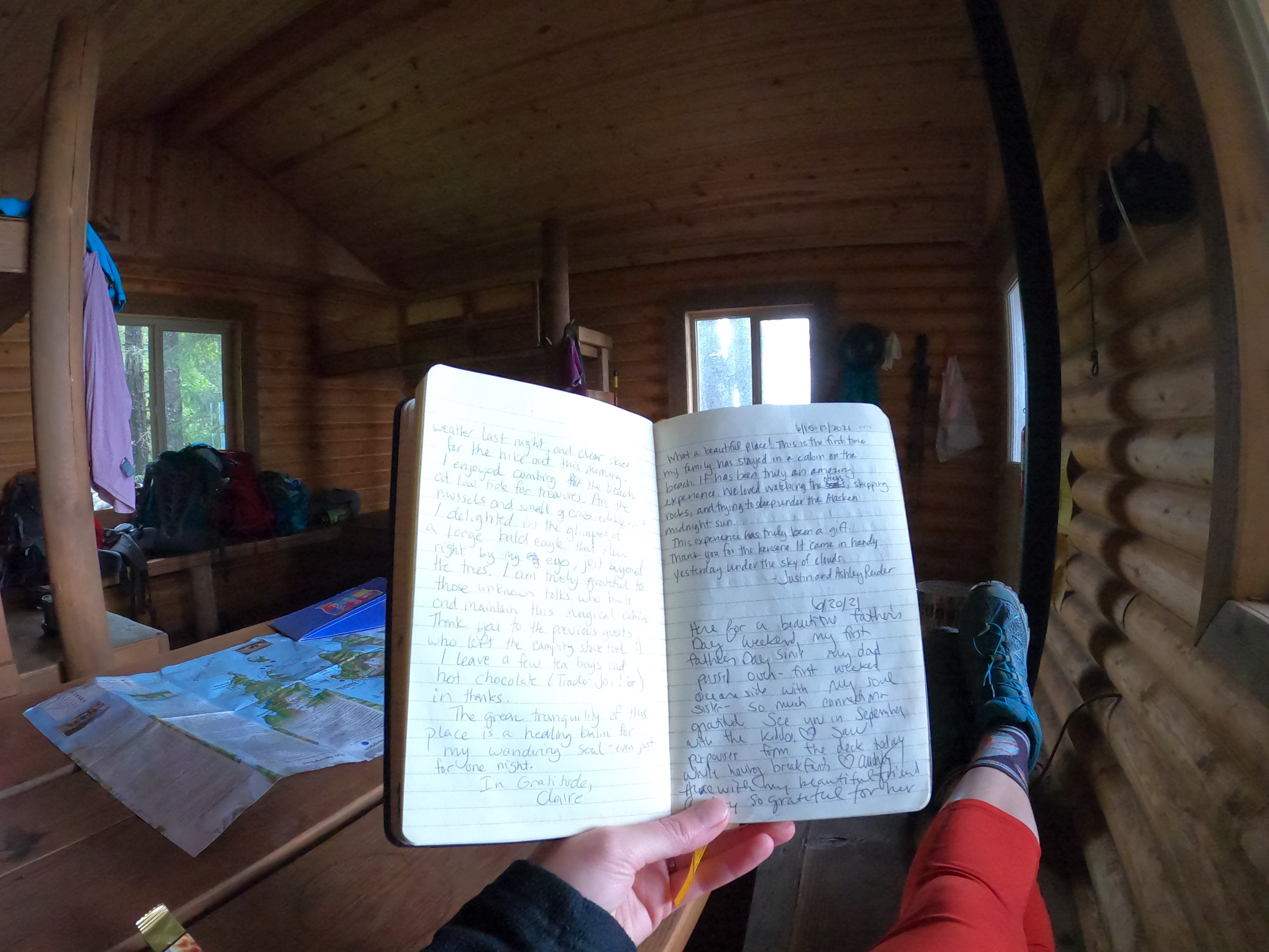

Journal entries - a wealth of knowledge

One of the first things I do when I arrive at a public use cabin is search for the cabin journal, or logbook. The State of Alaska provides journals at each public use cabin for cabin attendees to share their cabin experiences and provide area insights. Reading the handwritten words from strangers on each page is a welcome replacement to scrolling through social media feeds. Each person has a unique story and own perspective about their cabin stay. Often the entries provide a wealth of knowledge, from directions to the nearest freshwater stream to the most recent wildlife to have made an appearance in the area (from baby otters to angry bears). On our trip to Tonsina Cabin, we would have never found the most incredible waterfall without the captivating journal entry and directions. You’ll also find humor, artistic masterpieces, and playing card scores scattered throughout most journals.

Cabin celebrations - celebrate in [rustic] style Thinking of where to celebrate your next birthday? Although it may not be the first place to come to mind, consider booking a public use cabin for your next celebration or milestone - it’s bound to bring an extra ‘rustic’ flare to the festivities. For ease, book a drive-up cabin, close to town, to accommodate those that may not want to sleep on the cabin floor or in a nearby campground. If you are inviting people to stay, check the state website to confirm the cabin’s maximum occupancy. Alternatively, if that’s not your style, go big and hike in those 10 plus miles with your closest friends and enjoy the vista views through the cabin window. Each year I book one of the cabins at Eklutna Lake to celebrate fall-time birthdays, including my own. The fall colors at Eklutna get me every time. At our recent visit to the Tonsina cabin we presented our family member with a surprise birthday cupcake around the campfire – nothing tastes better than a surprise cupcake (squished or not) in the middle of nowhere. Don’t stop at birthday celebrations, others have used cabins for family reunions, retirement parties, marriage proposals and weddings. The only trick is to plan and book early!

Thinking of where to celebrate your next birthday? Although it may not be the first place to come to mind, consider booking a public use cabin for your next celebration or milestone - it’s bound to bring an extra ‘rustic’ flare to the festivities. For ease, book a drive-up cabin, close to town, to accommodate those that may not want to sleep on the cabin floor or in a nearby campground. If you are inviting people to stay, check the state website to confirm the cabin’s maximum occupancy. Alternatively, if that’s not your style, go big and hike in those 10 plus miles with your closest friends and enjoy the vista views through the cabin window. Each year I book one of the cabins at Eklutna Lake to celebrate fall-time birthdays, including my own. The fall colors at Eklutna get me every time. At our recent visit to the Tonsina cabin we presented our family member with a surprise birthday cupcake around the campfire – nothing tastes better than a surprise cupcake (squished or not) in the middle of nowhere. Don’t stop at birthday celebrations, others have used cabins for family reunions, retirement parties, marriage proposals and weddings. The only trick is to plan and book early!

About the Author: Kate Ayers has hiked, biked, skied, canoed, kayaked and water-taxied to more than 40 distinct Alaska Public Use Cabins. She developed her love of the great outdoors at a young age, while growing up in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. Now she aims to introduce her children to the same adventures, beauty, and appreciation for the awe-inspiring Alaskan outdoors.

-

-

Nancy Lake Cabin #3 - Kate Ayers

-

Late February, early March, is a great time for a stay in a public use cabin in Southcentral Alaska. Lakes have frozen over, there is more daylight, and temperatures are (usually) warmer than in January. The Nancy Lake Recreation Area is our go-to spot since it's close to Anchorage and there are a lot of cabins to choose from. As always, we booked early and snagged Nancy Lake Cabin #3. This cabin is unique in that there is not a land trail to it because it is surrounded by private property. In the summer, cabin goers must travel by water, most often in a canoe, to the lakeside cabin. In the winter, you have the option to ski, snowmachine, snowshoe, or fat tire bike across the frozen lake. The mode of transportation is not only determined by the season, but also the lake conditions during your stay.

Late February, early March, is a great time for a stay in a public use cabin in Southcentral Alaska. Lakes have frozen over, there is more daylight, and temperatures are (usually) warmer than in January. The Nancy Lake Recreation Area is our go-to spot since it's close to Anchorage and there are a lot of cabins to choose from. As always, we booked early and snagged Nancy Lake Cabin #3. This cabin is unique in that there is not a land trail to it because it is surrounded by private property. In the summer, cabin goers must travel by water, most often in a canoe, to the lakeside cabin. In the winter, you have the option to ski, snowmachine, snowshoe, or fat tire bike across the frozen lake. The mode of transportation is not only determined by the season, but also the lake conditions during your stay.

Cabin "hopping"

More often than not, public use cabins tend to be secluded, private, and off the beaten path. Cabins traditionally sleep 4-6 people, and at times up to 12 people. You can definitely travel with large groups, but if you prefer more privacy or a cabin of your own, it's difficult to find two cabins in close proximity (less than 1/8 mile) to one another. There are a few exceptions, such as the Byers Lake Cabin #1 and #2, K'esugi Ken cabins, and Bird Creek cabins (both located in campgrounds). Another exception was our experience with Nancy Lake Cabin #3 and Nancy Lake Cabin #4. Our "COVID-bubble" friends booked Nancy Lake Cabin #4 and it was great to hop back and forth between the cabins in less than a 5-minute ski.

Parent Perspective