Tangle Lakes

State and Federal lands in the Denali Highway region contain at least 900 known archaeological sites. Many of these sites are thousands of years old and contain information of great scientific importance to our understanding of Alaska's prehistoric past. When the highway opened in 1957, it provided new opportunities for the public to enjoy the region's exceptional natural and scenic values. The highway has also provided access for academic researchers and government archaeologists, who have worked to understand and preserve the physical evidence of Alaska's prehistory.

The Tangle Lakes Archaeological District Special Use Area (TLAD SUA) contains one of the largest concentrations of archaeological sites found along the Highway corridor. Each year the DNR Office of History and Archaeology assists the DNR Division of Mining, Land and Water in managing the area for maximum public access consistent with conservation of the district's cultural heritage.

Prehistoric Hunters in the Tangle Lake Archaeological District

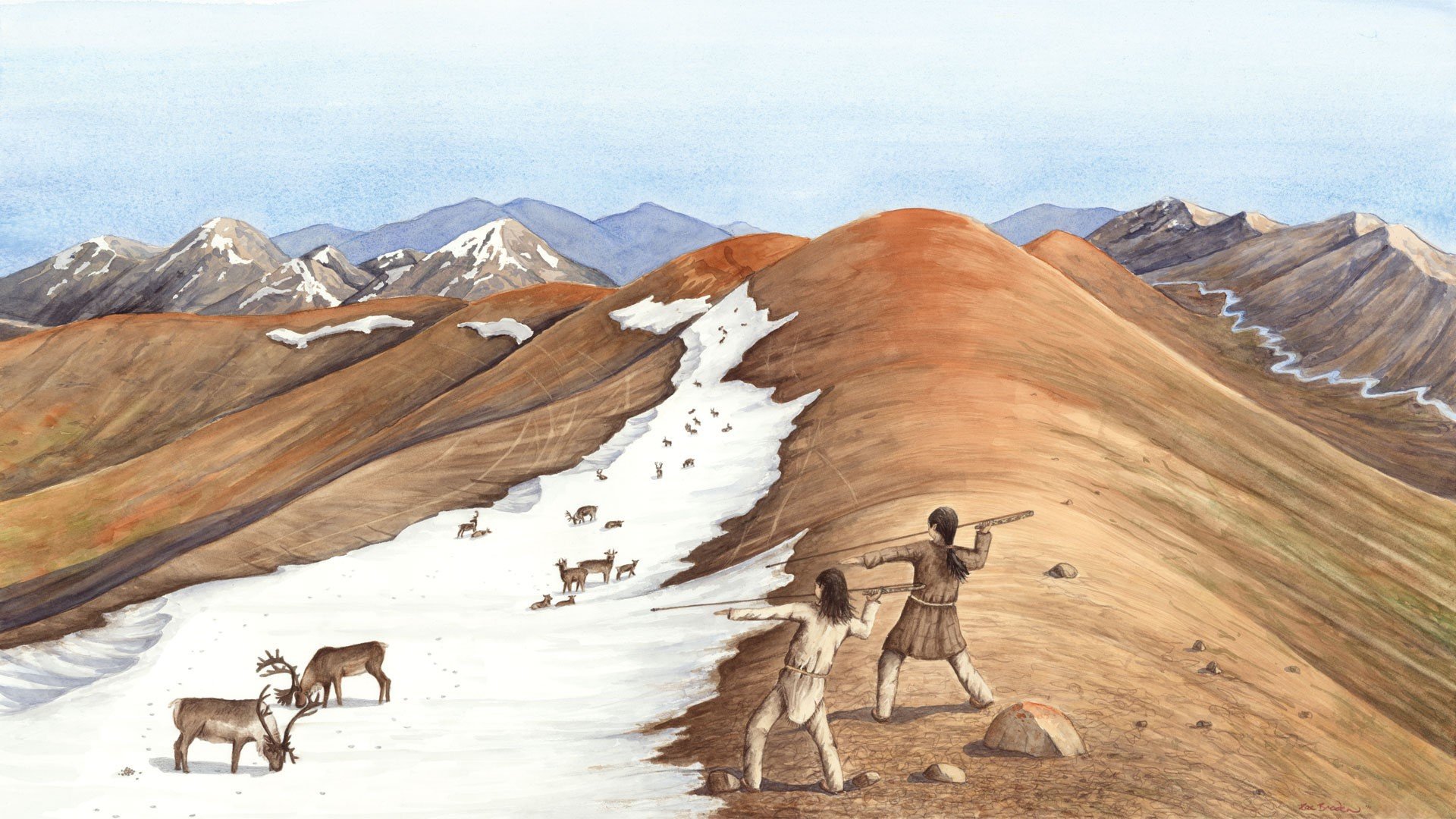

Until about 14,500 years ago the Alaska Range lay within the grip of vast glaciers formed during the last Ice Age. Along the Denali Highway these glaciers covered the entire landscape. After 14,500 years ago, the glaciers began to retreat, leaving behind hilly terrain formed from rocks, sand, and gravel dropped by the melting ice. Lakes formed in places where the ice sheets had weighted down or gouged out the mountain bedrock, while ponds filled low spots between the gravel hills and knolls. Within a few hundred years low brushy tundra began to grow on this new landscape and to support wildlife. Evidence from buried archaeological sites proves that prehistoric hunters began to visit the area at least 13,000 years ago. Caribou probably provided the most abundant prey, just as they do for modern sport and subsistence hunters. Based on finds made at mountain ice patches, we know that the bow and arrow did not appear in Alaska and the Yukon Territory until about 1,200 years ago. Before then, prehistoric hunters used a weapon system based on long, slender throwing spears archaeologists call darts. The darts were propelled using a device called an atlatl, or throwing board. This system provided extra leverage, speed and distance during the throw. Many prehistoric sites in the area are situated on overlooks from which the ancient hunters could scan the landscape for prey while they sat making and repairing their equipment. Most often preserved are small chips of stone discarded while tools and weapon tips were being made, along with rejected and broken tools. Several prehistoric stone quarries in the area provided a raw material with a fine, almost glass-like texture that was easily shaped by chipping off thin flakes. Seasonal trips into the uplands appear to have been carefully planned to provide opportunities to both harvest caribou and collect stone for making tools.

Prehistoric Camps

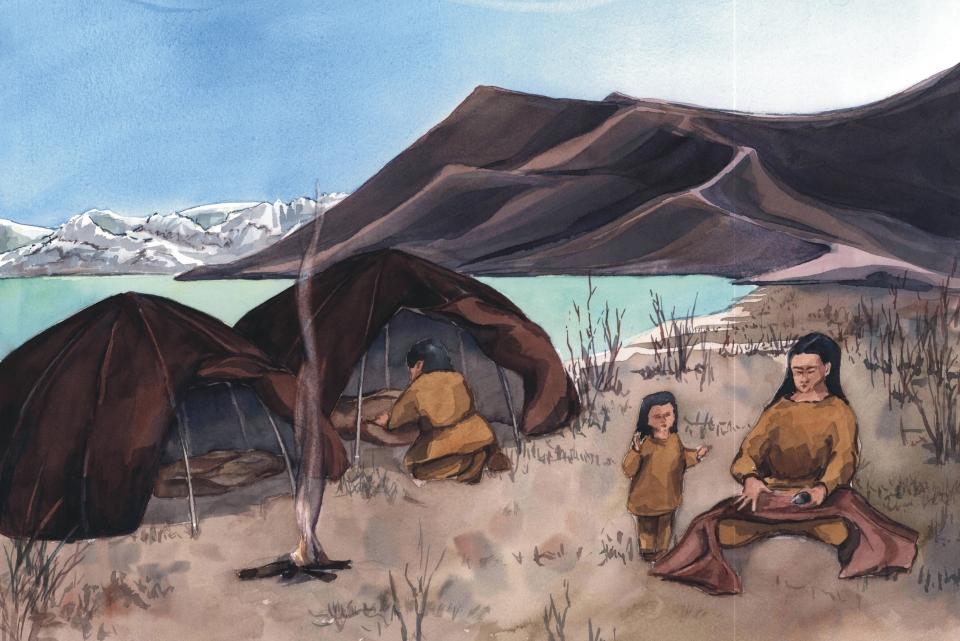

Prehistoric camp sites are common in the area. Most are found along lake margins or in close proximity to hunting overlooks. Buried camp sites usually feature one or more hearths used for heating and cooking, along with a scattering of chipped stone artifacts. The camp sites often contain a greater variety of tools than hunting overlooks. These may include several kinds of scrapers used to prepare hides for use in clothing, along with tools called burins and gravers used to work antler, bone or wood. Faint oval outlines interpreted as temporary house floors have been found at a few sites. These probably represent tents made of hides stretched over a wooden frame. Several camp sites, hearths and house floors in the District have been dated using the radiocarbon method. These dates prove that prehistoric people established camps in the District at 11,600, 10,300, 5,100, 3,030 and 1,100 years ago. Many others remain undated.

Denali Highway Archaeologists

Archaeologists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks discovered prehistoric sites in the Tangle Lakes area in 1957. Since then archaeologists affiliated with UAF, the Bureau of Land Management, Alaska Pacific University, Harvard's Peabody Museum, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the State of Alaska, and Texas A&M University have all carried out research or management studies in lands bordering the Denali Highway. Studies in adjacent areas like the Richardson Highway and the proposed Susitna-Watana dam impoundment have also contributed to our understanding. Recently, archeologists have discovered prehistoric sites in the alpine tundra of the Clearwater Mountains, including a quarry. Tantalizing leads at a few sites that may indicate human occupation older than 13,000 years ago are currently being explored.

Ice Patch Archaeology in the TLAD SUA

Some of the most important discoveries in the TLAD-SUA have come from ancient ice patches found in the Amphitheater Mountains. In a few locations, these ice patches survived without melting for several thousand years, but are now disappearing rapidly due to modern climate change. In summer, caribou use ice patches to escape from heat and biting insects. Stalking the caribou from above is relatively easy, so the prehistoric inhabitants frequently hunted the ice patches. They often lost equipment, such as darts, that are now being found by archaeologists as the ice patches melt. These artifacts are especially important because the ice has preserved organic materials such as wood, sinew, birch bark and feathers that are found nowhere else. Archaeologists affiliated with Alaska DNR have led the way in ice patch studies in the TLAD SUA.

Weapon tips and the Passage of Time

Archaeologists have traced the development of prehistoric hunting equipment through research in the TLAD SUA and many other locations throughout Alaska and Yukon Territory. Weapon tips, usually called projectile points by archaeologists, are among the easiest artifacts to study because they are relatively abundant and come in several distinctive forms. From the beginning of human history in Alaska up to about 150 years ago, there have been four main types: composite points, stone points, bone or antler points, and cold forged copper points. Details about the time span and functions of these types are debated in the scientific literature, but some general trends are fairly well proven.

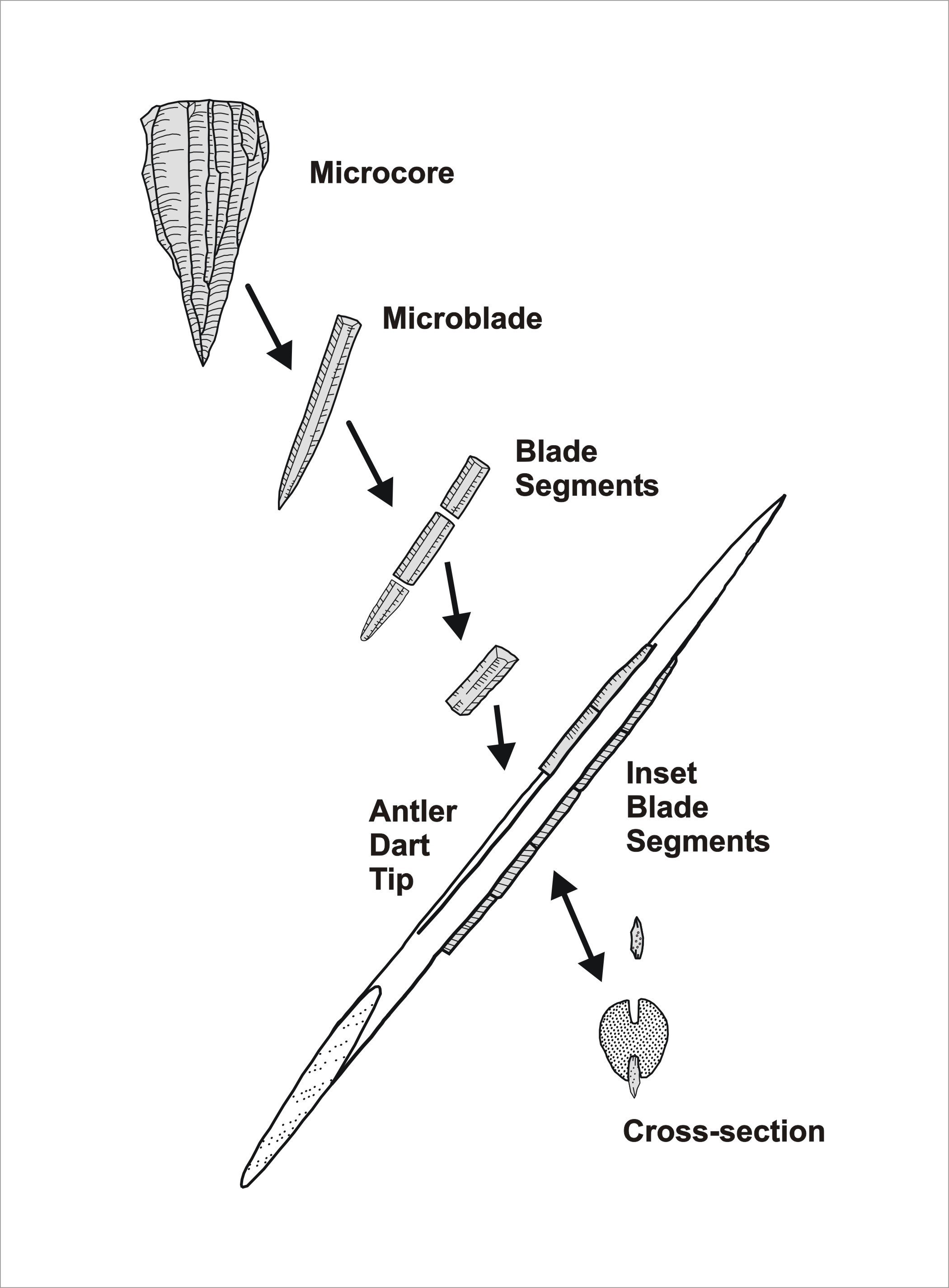

Composite Dart Point: this type may have been used as early as 14,200 years ago in Alaska. It consisted of a grooved and pointed bone or antler armature, into which were glued small slivers of glass-like stone called microblades. The microblades were specially prepared to be straight and slender. Broken into segments and inset into grooves along the sides of the point, the microblades formed a razor sharp cutting edge that could be repaired easily by replacing dulled, broken or missing pieces. Manufacture of composite dart points was a labor-intensive job and required access to high quality stone and organic materials. Despite this, microblades occur in Alaskan archaeological sites as recently as the last few thousand years. This suggests that composite points offered special advantages. One possibility is that the bone or antler armature was tougher and less prone to break than points made entirely of stone, especially at subzero temperatures during winter.

Flaked Stone Dart Point: this type occurs in archaeological sites during most of subarctic Alaskan prehistory. It was simpler to manufacture than the composite point and did not require materials of such high quality. The general outline of stone points and some details of the flaking changed over time, with some styles being characteristic of distinctive prehistoric cultures. However, most stone points were similar to the utilitarian lanceolate type shown here. Lanceolates have been found in Alaskan sites ranging in age from at least 13,500 years ago until the last few hundred years. Some have been found in ice patches still attached to the forward sections of darts. The points were attached to these foreshafts using sinew wrapping and spruce pitch glue.

Barbed Antler Arrow Point: about 1,200 years ago evidence for the introduction of the bow and arrow abruptly appeared in subarctic Alaska and the Yukon Territory. Arrow shafts carrying barbed antler, flaked stone and copper points have all been found at Yukon or Alaskan ice patch sites. The stone points tend to be smaller than those used on darts and some ice patch examples have notched bases that allowed for a more compact lashing onto the arrow shaft.

Cold Forged Copper Arrow Point: naturally occurring metallic copper is found at over 50 locations in Alaska, the Yukon and northern British Columbia. However, copper does not appear in subarctic Alaska archaeological sites until about 1,200 years ago; simultaneous with the introduction of the bow and arrow. Copper ornaments, awls, knives, needles and fishhooks also appeared at this time. The Ahtna Athabascan people of the Copper River Valley, located south of the Denali Highway, were renowned for their manufacture and trade in this material. Traditional Ahtna territory extends into the Denali Highway region, and a few copper artifacts, including a bracelet and an arrow point, have been found in lands surrounding the highway. Based on historical accounts, copper may have been a prestige material denoting high social status in traditional Athabascan society.

How Denali Highway Archaeologists Work

Prehistoric archaeology requires painstaking scientific work if we are to retrieve information that truly helps us understand Alaska's ancient past. All of the objects found in a site are mapped in three dimensions, usually to the centimeter, before they are collected. Extensive notes are also made recording their relationship to the surrounding environment, sediments and cultural features like hearths. Other samples, such as charcoal for radiocarbon dating, are also collected. Analysis of the artifacts, samples and map data is followed by publication of the results in the scientific literature. All of this work is done by an organized team and guided by a research design that has passed review by other professionals. Archaeological research on Alaska State Lands requires a special permit and is closely monitored by the DNR Office of History and Archaeology. This level of care is essential if we are to know the facts about Alaska's past and translate those facts into a better understanding of our state's cultural heritage.

Be an Alaska Heritage Defender

Archaeological sites are among the most fragile and non-renewable resources found in Alaska State Lands. Once destroyed, they are lost forever. Casual artifact collecting and erosion caused by off-trail ATV traffic are the biggest threats. In the TLAD SUA recreational users, including hunters and hikers, are the first line of defense for prehistoric site protection. Help benefit all Alaskans by following a few simple rules.

Please:

Ride ATVs only on designated trails

Avoid pioneering new ATV trails

Do not collect or disturb artifacts

Know the Law

It is illegal to damage, destroy or remove archaeological materials on Alaska State Lands. Violations are punishable with both criminal and civil penalties, including fines up to $100,000 (AS. 41.35.200-215).

To learn more about Alaska's prehistoric heritage visit https://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/oha/index.htm