Alaska Maritime Heritage Preservation Program

Preserving Alaska's Diverse Maritime Heritage

Tethered to Alaska's vast shorelines and major rivers are isolated and often historically underrepresented maritime communities whose lifestyles and cultures are as distinct as the regions in which they formed. From pack ice on the Arctic Coastal Plain, to salmon-rich riparian zones of the Yukon, Kuskokwim, and Bristol Bay, or temperate rainforests of Southeast Alaska, successful cultures thrived by using Alaska's diverse waterscapes, and passed their maritime knowledge from generation to generation.

The First Round Maritime Heritage Subgrants Awarded!

The Alaska Maritime Heritage Program accepted preservation and education grant applications until October 31, 2023. The Alaska Historical Commission and the Alaska State Museum grants committee reviewed and ranked many excellent maritime proposals in November. By December, the State Historic Preservation Officer made the final decisions based on grant criteria from the National Park Service.

Awards ultimately went to 5 Maritime Heritage Preservation projects totaling $85,272 and 10 Maritime Heritage Education projects totaling $209,697. Most projects will commence in February 2024 and be completed by June 2025.

The Alaska Maritime Heritage Program congratulates the first round of education and preservation subgrantees!

Maritime Heritage Grantees, Start Here!!

Grants Management Orientation

Kathleen Tarr and Jean Ayers, OHA Grant Administrators

May 17, 2024

Alaska Maritime Heritage Preservation Subgrants

| No. | Subgrantee | Community | Project Title | Amount |

| 1. | Eldred Rock Lighthouse Preservation Association | Haines, Alaska | Gutter Cornice Repair Project | $15,650 |

| 2. | Sitka Maritime Heritage Society | Sitka, Alaska | Restoration & Sprinkler System for historic Japonski Island Boathouse. | $20,000 |

| 3. | Gastineau Channel Historical Society | Juneau, Alaska | Sentinel Island Light Station Support Building Rehabilitation | $16,700 |

| 4. | City and Borough of Wrangell | Wrangell, Alaska | Following the Star: Documenting the Legacy of the Shipwreck of the Star of Bengal | $23,720 |

| 5. | Cape Saint Elias Lightkeepers | Cordova, Alaska | Saving the Cape St. Elias Light Station Boathouse | $9,204 |

Alaska Maritime Heritage Education Subgrants

| No. | Subgrantee | Community | Project Title | Amount |

| 1. | Eldred Rock Lighthouse Preservation Association | Haines, Alaska | Eldred Rock Lighthouse Video and Historic Tour Project | $30,700 |

| 2. | Kodiak Alutiiq Museum | Kodiak, Alaska | Qayat Exhibit | $22,518 |

| 3. | North Star Community Foundation | Fairbanks North Star Borough | Interpretive Services for the SS Nenana | $5,000 |

| 4. | Sitka Maritime Heritage Center | Sitka, Alaska | Sitka's Native Maritime History | $20,000 |

| 5. | Bristol Bay Heritage Land Trust | Dillingham, Alaska | Sailing with the Star Fleet: Axel Widerstrom | $10,000 |

| 6. | Haida Canoe Revitalization Group | Kasaan, Alaska | Kasaan Canoe Documentation Project: Unlocking the Wisdom of an Ancient Canoe | $35,629 |

| 7. | Ketchikan Museums | Ketchikan, Alaska | History Afloat: Ketchikan's Maritime Heritage Project | $9,250 |

| 8. | Kodiak Maritime Museum | Kodiak, Alaska | Alaska Limited Entry Program Exhibit | $23,000 |

| 9. | Bristol Bay Historical Society & Bristol Bay Heritage Land Trust | Naknek, Alaska | Sailing Back to Bristol Bay, Phase 2 | $38,000 |

| 10. | Museum of the Aleutians Association | Onalaska, Alaska | Sharing Unangax̂ Heritage at the Udax̂tan Village Site | $15,600 |

Alaska History is Maritime History

Uncounted cultural and historic maritime properties represent areas associated with significant contexts that shape Alaska's history: Indigenous technology, subsistence strategies, sea otter trade, Pacific World exploration, commercial whaling, seal hunting, gold rush transportation, navigation, communications, law, engineering, community settlements, commercial fishing (cod, salmon, halibut, crab, clams, herring, pollock, etc.), military, marine science and conservation, art and advertising, tourism, shipping, and living maritime history. Alaska's maritime resources represent Alaskans' 15,000-year bond with the sea.

Alaska's Maritime Heritage at Risk

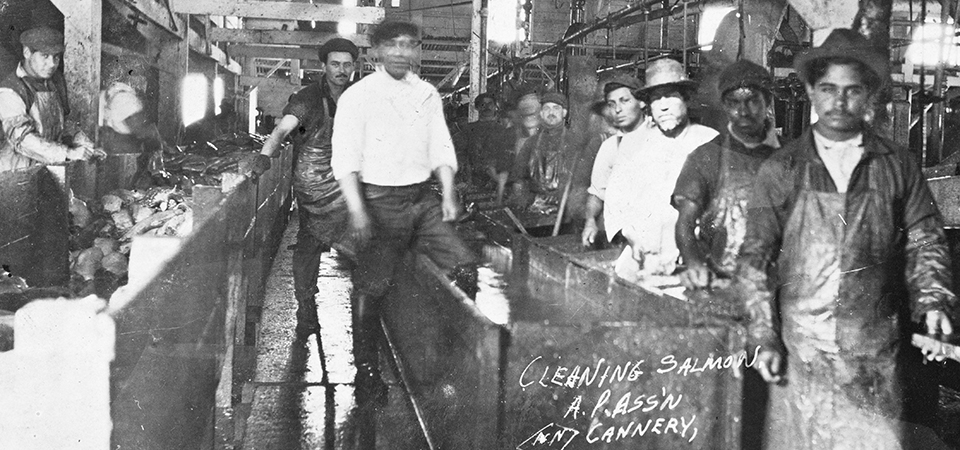

Far too many of Alaska's maritime historic properties remain unlisted, underrepresented, and unprotected. Only three canneries–Kukak, South Naknek, and Kake (also an NHL)–are listed in the National Register, despite the canned salmon industry's century-long influence, multi-generational and multicultural involvement, and massive historical footprint. Up to 3,000 shipwrecks and an untold number of inundated terrestrial sites may be located within Alaska's 47,000 miles of tidal shoreline. Moreover, maritime heritage sites within the dynamic coastal zone are vulnerable to damage or loss through natural and human forces. Subsiding lands around the Gulf of Alaska resulting from the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake, as with previous seismic events, placed many coastal sites within reach of storm waves. Rising sea levels and changing storm patterns due to climate change further alter the coastline, speeding erosion and submerging or destroying many cultural sites. Changing currents may produce negative impacts, including ocean acidification and expanding the range of invasive marine organisms. Some human impacts include increasing infrastructure for mineral and oil extraction, the laying of subsea communications cables, and bottom trawling. Concurrent with these impacts, the recent diffusion of new and inexpensive remote sensing, navigation, and diving technologies has removed many barriers that previously prevented site discovery and exploration. This has resulted in new discoveries and knowledge but also has increased incidents involving the disturbance of protected maritime heritage sites.

A New Program for Alaska's Maritime Heritage Preservation

To preserve and interpret Alaska's rich maritime heritage the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) and the State Libraries, Archives, and Museums (LAM) announce the launch of the Alaska Maritime Heritage Preservation Program. This program is designed to protect Alaska's maritime resources and advance public awareness of Alaska's nationally significant maritime properties, collections, traditional skills, and knowledge.

Alaska Maritime Heritage Preservation Program goals:

- Building a network of statewide partners dedicated to preserving Alaska's rich maritime heritage and increasing public appreciation for Alaskans' long and multifaceted relationship to the water.

- Continuing support and resources for projects that identify, document, and interpret Alaska's maritime resources, such as historic, cultural, and archaeological properties, archival documents, oral history, folklore, and traditional lifeways.

- Increasing the visibility of Alaska's maritime past (and present) by preserving and interpreting archaeological and historical properties and maritime cultural landscapes along Alaska's vast coastline.

- Sharing the stories of Alaska's longstanding human history that left a legacy of tangible maritime heritage and a diverse, yet often underrepresented, maritime culture.

- Encouraging the protection of Alaska maritime physical resources, collections, and seafaring and ecological knowledge to enhance understanding of Alaska's maritime legacy and lessons learned for future generations.

New Program New Opportunities

The Alaska Maritime Heritage Preservation Program will offer Alaskans two new grant opportunities for preservation and education projects. Of the total $342,500 federal award, $15,000 will support in-house projects at the Alaska State Museum. The remaining $327,500 will be subgranted to support preservation and education projects statewide. The in-house and subgrant programs will empower communities to safeguard and share a maritime heritage associated with their unique region, culture, and lifeways.

Who Can Apply

The new competitive grant program will provide support, expertise, and resources to state governments, cultural and academic institutions, 501(c)(3) nonprofits, local governments, and Tribes throughout Alaska's varied geographic and cultural regions.

Minimum and Maximum Grant Awards

Applicants for preservation grants can request from $10,000 to $50,000 and applications for education grants can request from $5,000 to $50,000. The SHPO anticipates $100,000 in available funds for preservation projects and $227,500 for education projects.

Matching Requirement

Both the preservation and education grants are 1:1 matching requirements. Each federal dollar must be matched by one non-federal dollar. Match may be in the form of cash or in-kind donations of time, goods, or services. So, a grant proposal for $10,000 must support a $20,000 project.

When to Apply

The SHPO will accept maritime preservation and education grant applications from August 1, 2023, to October 31, 2023. Projects should be ready to commence by February 2024, and be completed by June 2025. E-mail applications to dnr.oha@alaska.gov.

Alaska Maritime Heritage Preservation Grants

The Program's Preservation grants are for projects that advance Alaska's maritime heritage through public education for a wide audience and at least one of the following elements:

1) Identify, document, and evaluate archaeological and historic marine resources;

2) Research, record, and plan for marine resource preservation;

3) Repair, rehabilitate, stabilize, or maintain historic maritime resources with limited reconstruction or other capital improvements per the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation and Standards for Historic Vessel Preservation Projects.

Eligible project examples include but are not limited to surveys that identify localized marine resources, National Register nominations, feasibility studies, architectural and engineering services, and acquisition of marine resources for preservation purposes.

To learn more about Alaska's Maritime Preservation Grant, contact: State Historian Katie Ringsmuth at dnr.oha@alaska.gov.

Alaska Maritime Heritage Education Grants

The Program's Education grants are for projects that advance Alaska's maritime heritage through public education and at least one of the following elements:

1) curation, interpretation, and public access to collections;

2) Planning, developing, interpreting, and maintaining definable geographic areas encompassing one or more cultural and historic themes expressed through the area's remaining historic maritime properties;

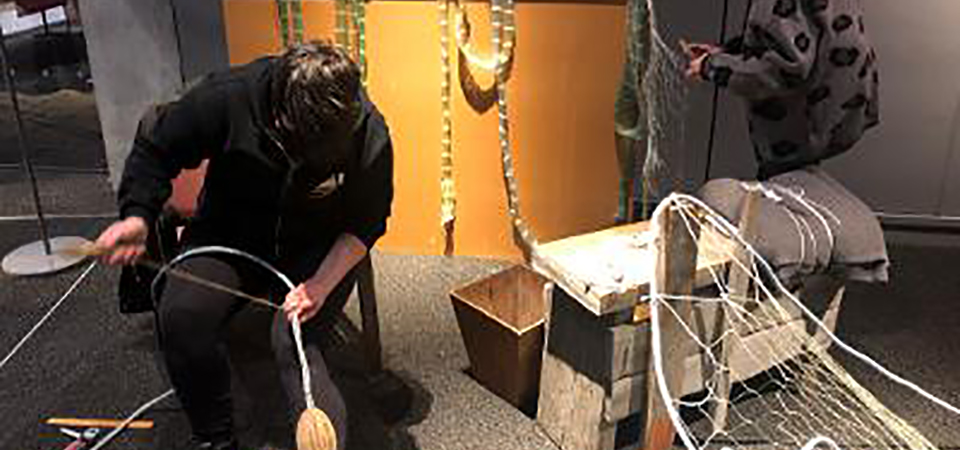

3) Developing and implementing waterborne-experience programs that include instruction and hands-on participation;

4) Participatory programs interpreting current scholarship to enhance public understanding and appreciation of Alaska maritime history;

5) Activities designed to encourage preserving traditional maritime skills and teach continuing generations those skills, techniques, and methodologies, or

6) minor improvements to existing educational facilities and exhibit spaces of maritime museums, organizations, or historical societies.

Eligible project examples include but are not limited to participatory archaeology, treatment of and access to maritime collections, interpretive signage, walking tours, podcasts, oral histories, story maps, exhibitions, lecture series, poetry readings, storytelling, public demonstrations, shipwright workshops, art classes, sea shanties, and minor improvements to existing educational facilities and exhibit spaces.

To learn more about Alaska's Maritime Preservation Grant, contact: State Historian Katie Ringsmuth at katie.ringsmuth@alaska.gov or Alaska State Museum Curator Mary Irvine at mary.irvine@alaska.gov.

How To Apply

Program staff held a "how to apply" interaction session via Microsoft Teams. The virtual session provided technical assistance to prospective applicants, discussed differences between the two grants, highlighted eligible projects, and explained the grants' matching requirements. Click here to view the recording of the first session.

A second session took place on September 21, 2023 entitled Preservation and Education Maritime Grants 101: How to Apply. Click here to view a recording of the second session.

To set up a Maritime Education or Preservation grant consultation with program staff, or request an invite to the next Maritime Grants Learning Session, email dnr.oha@alaska.gov.

Public Education Requirement

Whether applying for preservation or education grants, all subgrant projects must advance Alaska's tangible maritime heritage through public education. This aspect will be especially beneficial for communities developing heritage tourism programs around their historic properties.

Important Links

Federal Award Information for Preservation Grants P22AS00347

Federal Award Information for Education Grants P22AS00355

Home | Alaska State Museums

Our Storied Places

Defining Historic Maritime Resources

Grant Program Requirements

Program Funding Source

Support for the Alaska Maritime Heritage Preservation Program comes from the National Maritime Heritage Grant Program was established by the National Maritime Heritage Act of 1994 as a cost-sharing grant program administered jointly by the National Park Service and the U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration (MarAd). The program issued one round of grants in 1998 and then went dormant until it was re-established in 2013. Program funding is provided by the proceeds of scrapped ships from the National Defense Reserve Fleet through a Memorandum of Agreement between the National Park Service and MarAd. The program's purpose is to provide funding for a wide range of education and preservation projects that promote and educate the public on America's extensive maritime heritage. To help meet this goal, the total dollar amount of grants awarded in a fiscal year must be equally divided between education projects and preservation projects.

Historic Context: The Significance of America's Maritime North

While Alaska's "Last Frontier" moniker is popular, it remains historically problematic. The frontier interpretation ignores a history that came eastward from Asia. And, when historians position Alaska as a periphery of western expansion, they exclude Alaska's 30,000-year-old history as a geological, ecological, and cultural bridge connecting America to two trans-global spheres: the Circumpolar North and the Pacific Rim. Explaining Alaska History through a maritime lens dismantles Alaska's frontier myth and moves the Maritime North from the fringe to a central position in American history. Ultimately, the Alaska Maritime Heritage Preservation Program will support projects that increase awareness of Alaska's significance to the maritime heritage of the United States.

Embedded in Alaska's coastal communities are layers of evidence documenting a human history that began with the retreat of Pleistocene glaciers and the return of salmon, sea mammals, and other marine resources that recolonized a post-ice age landscape. Along coastlines and rivers that endure a constant cycle of freeze and thaw are eroding middens, villages, fish traps, and bidarkas. Examined with oral testimony, cultural ceremony, and traditional knowledge, these resources bear witness to the marine subsistence strategies and ecological realms of the past that explain Alaska's diverse indigenous landscapes and ground-truth theories on the peopling of the Americas.

Unlike familiar trails that penetrated the American West, European expansion into Alaska followed routes through the Asian Far East. Like Columbus, who connected continents on both shores of the Atlantic, Vitus Bering linked a vast waterscape where "imperial and personal contests played out in isolated bays and coastlines." Russian fur-hunters sought valuable sea otter pelts along coastal Alaska, while the Russian Orthodox Church sought converts. Both relied on local Native people and their knowledge of the sea for hunting, food, and transportation. Russian settlements in the Aleutians, Kodiak, Resurrection Bay, and Sitka left a legacy of colonization preserved in maritime resources, including remnants of pier foundations, shipyards, artels, redoubts, chapels, and shipwrecks. Captain Cook's voyages in the 1770s and the subsequent convergence of European explorers and exploiters -- British, Spanish, Russian, French, and American -- transformed Alaskan seaports into international hubs connecting the Far North to the emerging Pacific World. These maritime traders plied the waters for profitable commodities while bringing cultural, environmental, and biological changes to those regions. Investigations into early maritime trade challenge the entrenched historical interpretation that Alaska served simply as the nation's last frontier rather than America's link to the World.

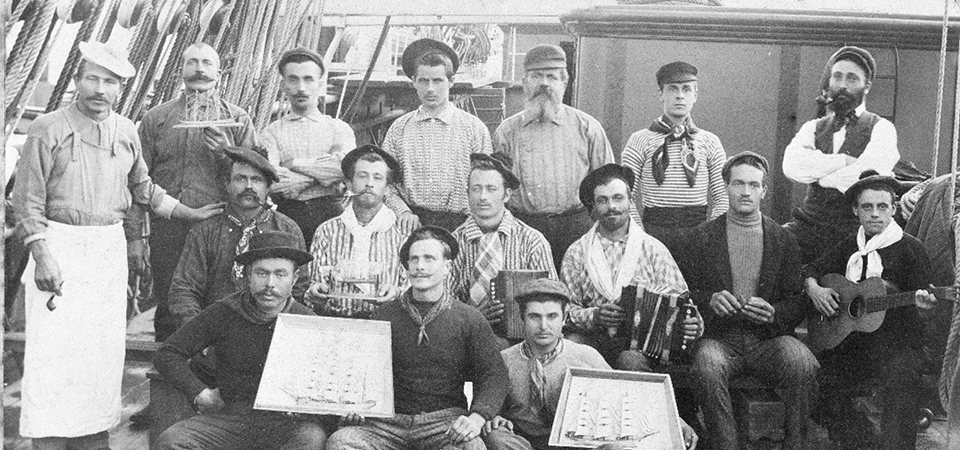

The expansion of New England whaling into the Arctic for sperm and bowhead whales in the 1840s led to the commercial entry of the United States into the Maritime North, prompting American territorial interests in Alaska. Innovations such as trypots allowed Atlantic whalers to voyage further and render blubber at sea. Decades of whaling nearly drove the bowhead to extinction, impacting the Inupiat's 1000-year whale-dependent lifeway. Arctic whaling served as a backdrop for the last shot of the Civil War and presented fugitive slaves arriving in New Bedford an escape route, characterized by maritime historians as the "Underground Railroad Afloat." In 1894, Brigadier General Frederick Funston described an Arctic whaling camp as "more cosmopolitan than any other place on the globe." This underscores maritime curator and historian Joel Stone's observation that "the maritime community has always been the earth's most diverse and cosmopolitan population, going back to the days of seagoing vessels where Caucasians, Asians, and Africans worked together for centuries."

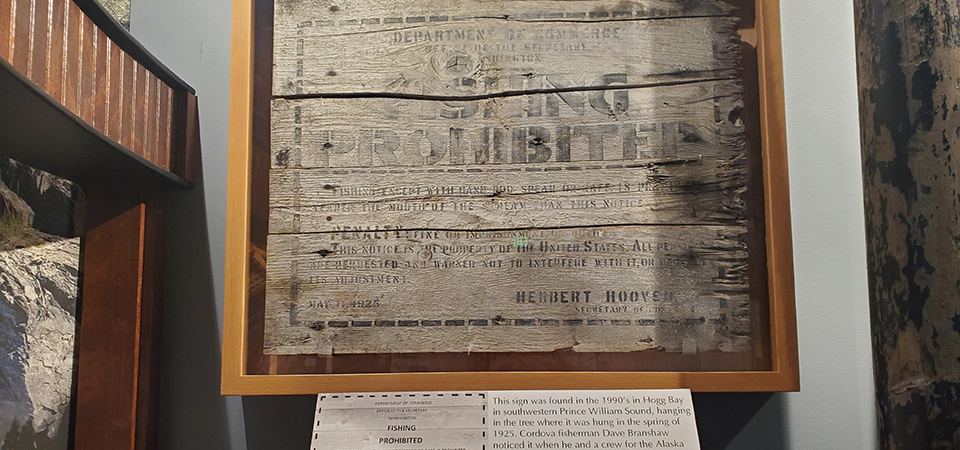

To Interior Secretary William Seward, Alaska served as a stepping-stone, linking America to Asia and, importantly, represented new markets for the industrializing North, which led to the transfer of Alaska from Russia to the United States in 1867. Mercantile fortunes made during the California gold rush set the stage for Alaska Commercial Company to make millions harvesting Pribilof fur seals and profited even more by selling supplies to prospectors during Alaska's gold rush. Commercial steamships and riverboats transported hopeful miners from West Coast ports up the Yukon, Tanana, and Nenana rivers where river tributaries became roads and boats were a miner's only vehicles. Gilded Age salmon canneries -- with pulsating machines, efficient fishing, processing, canning and marketing methods, and a multiethnic labor force -- represented the Industrial Revolution of the North. This pursuit introduced new boats and mechanized assembly lines, replaced skilled workers with steam-powered machines, built electrical, water, and communications systems, and applied science to manage fish runs. Salmon packers sold canned fish to markets worldwide through a large-scale transportation network. Use of traps left few fish and little profit to local Alaskans, prompting a political fight for America's 49th star.

Meanwhile, the federal government built lighthouses, charted the coastline, funded harbors, and, with growing international tensions, established military bases along the coast as part of a defense system to protect against possible invasion. With the Aleutian Campaign's proximity to the Pacific Theater, the battles of Attu and Kiska command high profile in nationally significant maritime history. Likewise, the little-known removal of Unangax people under Executive Order 9066 and their wartime internment in abandoned canneries warrant historic evaluation and stand out as a difficult maritime topic worthy of public education and mindful interpretation. Conversely, oil-soaked sea otters during the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill sparked a 24-hour news cycle and symbolized the nation's modern environmental movement.

Alaskans continue to make a living from the sea. Dutch Harbor is the largest fishing port in the nation, Kodiak shelters the largest fleet of fishing boats on the west coast, and Bristol Bay's sockeye runs are the largest on Earth. Tourism, one of Alaska's main economic engines, is largely driven by people opting for time on the water: from kayaking in quiet bays to cruising in city-sized ships. Ninety percent of Alaskans receive consumer goods shipped in containers from global suppliers. Importantly, as climate change causes Arctic ice to thin, the famed Northwest Passage will open to marine shipping and cruise ships, reinforcing Alaska's link to the world and increasing our vitality nationwide. Each of these aspects of Alaska contains a legacy of tangible maritime heritage significant to our nation. Significantly, they serve as contexts to better interpret, evaluate, and understand Alaska's rich maritime resources on a national and international scale.