Castle Hill Archaeological Project

With its commanding view of Sitka Sound, Castle Hill has long been a defining landmark of the Sitka landscape. This rocky sixty-foot-high promontory was once the colonial capitol of Russian-America and the location of events which shaped U.S. history. Today Castle Hill is part of Baranof Castle State Historic Site and is designated as a National Historic Landmark. During the summers of 1995, 1997, and 1998, archaeologists from the Office of History and Archaeology (OHA), assisted by students and volunteers, excavated deposits dating to the early nineteenth century and earlier to recover artifacts and information. The excavations were part of Section 106 compliance work prior to a major development project to improve public access to the Baranof Castle State Historic Site.

Despite extensive disturbance from prior construction at Castle Hill, the excavation team discovered the buried ruins of four Russian-American Company buildings with associated floor and trash deposits. Radiocarbon dating of an adjacent midden deposit indicates that Tlingit Indians occupied Castle Hill as early as 1,000 years ago. The artifacts collected from Castle Hill will soon be transferred to the University of Alaska Museum of the North in Fairbanks for permanent repository storage. There, the collection will be available for study by qualified researchers. The information obtained from the archaeological project and analysis of the collection has led to a clearer understanding of patterns of habitation and use of the area, the varied industries of the Russian-American Company, and day-to-day lives of workers (primarily Natives and Creoles) during the Russian period.

Raven's Tail, Alaska State Museum

A selection of artifacts from the Castle Hill collection are on exhibit at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau. These include a fragment of Ravens Tail Robe, a rare example of a southeast Alaskan weaving style that went out of use by the 1820s. This weaving style was replaced by the more well-known and ubiquitous Chilkat Blanket. Prior to this discovery, no examples of Raven's Tail weaving were known to be in existence in Alaska and only 11 examples were known to be in museum collections worldwide. Cheryl Samuel, an expert weaver, studied examples of Raven's Tail weaving including the fragment collected at Castle Hill. She reverse-engineered the weaving technique and taught others through a program co-sponsored by the Alaska State Museum and the museum's friends organization. This program helped revitalize this weaving technique that had previously been lost to history. The Alaska State Museum has cared for and conserved the Castle Hill Raven's Tail fragment since its excavation. OHA formally transferred this fragment to the Alaska State Museum in 2016.

Also on display at the Alaska State Museum are several items excavated from Castle Hill on long-term loan from OHA. These include two carved ivory bears, Tlingit and Russian game pieces, Russian pipes, samovar parts, and several other examples of Tlingit and Russian material culture.

-

Archaeology at Castle Hill: Window to the Past

-

In 1995, archaeologists began a testing program to locate and evaluate buried deposits at the former Russian-American capitol. Initially, work focused on top of the hill, within a stone enclosure constructed in 1966-67 for the Alaska Centennial celebration. Most deposits were largely disturbed, but the discovery of a possible cellar floor from the Russian period suggested that other deposits of intact materials might be present. Archaeologists returned to Castle Hill during the summers of 1997 and 1998 to conduct larger scale excavations in advance of construction work to improve access to the site.

In 1997, archaeologists removed and screened the soil from 52 one-meter squares on a natural terrace near the northeast base of the hill. The discoveries in this area far exceeded expectations. The archaeologists discovered undisturbed Russian period artifacts in a layer 10-18 inches below the surface, along with axe-cut timbers and stains from decayed support posts. Within this deposit, the excavators discovered the base of a brick metal workers' smithy (kiln) surrounded by copper slag and waste, a copper ingot, iron bar stock, and metal working tools. They also found finished and unfinished sheet copper implements, along with scrap from their manufacture. The importance of the deposit was enhanced by preserved organic items such as textiles, cordage, rope, hair, fur, feathers, leather items, worked wood, and exotic botanical materials. This extraordinary preservation resulted from elevated soil acidity (pH = 5.9) caused by the large number of axe-cut spruce wood chips in the soil. The organic layer contains a combination of domestic and industrial trash, mixed with materials from nearby building demolition and construction.

In 1998, archaeologists opened an additional 103 one-meter squares east of those excavated the previous year. Excavations in this area, beneath a heavily used park trail, revealed the ruins of at least four Russian period buildings. The floor deposits suggest that at least two of the buildings were workshops. One ruin, mostly destroyed by gardening and trail construction, is believed to represent the last Russian building to occupy the site. The metal workers' smithy identified in 1997 was fully excavated, along with the building which housed it. The intact forge was re-buried at the end of the season with hope that funding might be found for a viewing shelter and interpretive exhibit.

Archaeologists believe that, during the 1820s and 1830s, artisans and craftsmen worked in shops at this location. Manufacturing and repairing industries included coppersmithing, blacksmithing, shoe and leather goods manufacture and repair, and woodworking. The recovery of several modified bird feathers suggest that pen nibs were manufactured at the site as well. Concentrations of lead spatter in the soil document the pouring of musket balls, or possibly lead seals used in the bundling of fur bales. Under orders of the Manager, workers labeled the lead seals with the initials of the Russian-American Company, along with letter codes to indicate the origin, type, and quality of furs. 1830 marked the end of a period of renovation and new construction that had begun in 1818. Baron F. P. Wrangell, who was Chief Manager of the Russian-American Company from 1831 to 1836, noted that in 1833 the population of Sitka was comprised of 847 persons (Wrangell 1980:4).

Historic accounts indicate that Natives and Creoles (the children of Russian men and Native women) comprised a large percentage of the workforce at New Archangel. Many Alaskan Native items were found among the items in the workshop area. Ivory and bone carvings identical to examples from Northwestern Alaska were recovered, along with several stone dart points. Items associated with the Bering Strait and Aleutian Islands Natives were found, along with spruceroot basketry and woven cedar bark matting of local manufacture. A notable discovery was a portion of a "Raven's Tail" robe. Only 12 examples of these rare goat wool robes are known to exist. Raven's Tail weaving was done by Tlingit Indians until replaced by Chilkat weaving around 1820. The Castle Hill specimen has design elements essentially identical to those portrayed on Chief Katlian's robe in an 1818 watercolor by the Russian artist Tikanov.

During the early nineteenth century, New Archangel (the "Paris of the Pacific") was the largest and most cosmopolitan settlement in the North Pacific. The settlement was a port of call for traders who also visited Europe, Asia, and the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), and settlements along the North American west coast. The Castle Hill artifacts include coconuts, hazelnuts, bamboo, and exotic woods. Three Japanese coins ("Kan-ei Tsuho") from Castle Hill may document an occasional but forbidden trade with the islands of Japan. Scholars from the Japanese Museum of Ethnology are assisting with the identification of these coins, which were minted during the Edo period (circa 1638-1868).

-

-

The Workers and Industries of New Archangel

-

Between 1799 and 1867, the Russian population in the American settlements ranged from 225 to 823, comprising less than 8% of the total censured population. K.T. Khlebnikov, chief of the Sitka office (1818-1838), recorded information on the population, buildings, industries, and living conditions in Russian-America. His writings help us to interpret the archaeological materials from Castle Hill and, conversely, the archaeology adds depth and color to the written record.

The Blacksmiths in Sitka worked at three forges, repairing sailing ships, making and repairing axes, and making plough shares for the California trade. The coppersmiths also had three shops, staffed by Creole apprentices and masters. They manufactured copper and tin cauldrons, cups, teapots, coffee pots, siphons, funnels, and other types of vessels in two of the shops -- both local use and for trade in the outlying settlements. The copper forge uncovered by archaeologists in 1997-1998 was probably inside one of these two shops mentioned by Khlebnikov. In the third shop, coppersmiths casted small ships' fittings and bells.

Many of the specialized trades in Sitka were directly or indirectly related to the fitting and repair of ships. Coopers repaired barrels for the shipping of grains to the colonies. Less commonly, they manufactured new barrels, tanks, and other ships equipment. Woodworkers and boat-wrights made pulleys, blocks and capstans, pumps, rowboats, launches, whaleboats, and skiffs. Portions of barrels, pulleys, and implement handles uncovered by archaeologists may help us to better understand the scope and technology of these industries. A thick layer of wood chips at the site may partially relate to the construction of log buildings during the company's ambitious construction during the 1820s and 1830s.

Rope makers at Castle Hill manufactured various sizes of cordage and rope for logging and use on ships. We know from the archaeology that workers also used Native-made cordage of cedar bark and spruce root. According to Khlebnikov, candle makers made candles from California tallow to be used in houses and on ships. Archaeologists collected several tallow samples from candlestick holders at Castle Hill for analysis. Painters and assistants made paint from coconut or hemp oil. Both buildings and ships were frequently painted to prevent them from rotting in the damp climate. An active trade with the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), and perhaps paint making, is evidenced by the archaeological recovery of coconuts in the Castle Hill deposits.

-

-

Public Education and Interpretation

-

Sitka had an estimated 200,000 visitors in 1997 and again in 1998. Some indicated to public officials that the dig was a highlight of their visit. From its inception, the Castle Hill Archaeological Project had public involvement and education as priorities. At Castle Hill, local residents were invited to work at the dig under the supervision of trained archaeologists. It was an opportunity to teach site stewardship and basic principles of archaeology. Experienced archaeologists and historians from other communities also participated in the excavations as volunteers. Castle Hill archaeologists collaborated with local groups to offer classes, lectures, site tours, and museum exhibits.

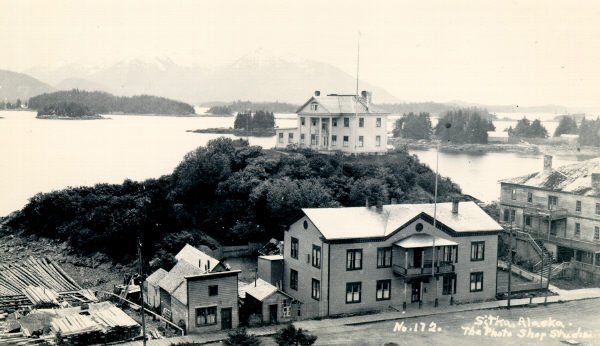

If Castle Hill was standing today; composite image, Sitka Historical Society The excavations have produced the largest collection of 19th century Russian-American materials from Alaska. The collection, due to its size and diversity, will be the focus of scholarly research for many years. The rich body of information contained within the Castle Hill collection may help promote a better understanding of the day-to-day lives and industries of the working class employees of the Russian-American Company. The archaeological data compliments the archival record, which focuses on important people and events or the broader view of history. The collection already is providing insights on architecture, trade, industry, food preference and preparation, adaptive re-use of material items, and consumer choices in Russian-America.

-

-

History

- Contact History

-

At the time of first European contact (ca. 1795) Noow Tlein, now called Castle Hill, was occupied by the Kiks.ádi clan of the Tlingit. At that time, this rocky 60 ft. high promontory at the edge of Sitka Harbor was surrounded by water on three sides and was cut off from the mainland by high tides. It wasn't until the 1960s that fill was placed around the base of the hill, resulting in its present appearance. Oral history states that four Kiks.ádi clan houses were located on the hill at Noow Tlein. These were "On-the-Point House," "Inside-the-Fort House (Nu-to-hit)," "Herring Flutter House (Yah-ooo-hit) ," and "Sun House (Gagan-hit)" (Andrews 1960:24). Andrew Hope (1967) of the Sitka Kiks.ádi's Point House, in relating the story an elder told to him, states that there were four "communal" houses on top of the hill and a fifth house on a natural bench toward Indian River. He stated that other houses were located "across from the cold storage, " and that some chiefs didn't like the idea of carrying water up the hill (Hope 1967).

The hill, with its commanding view of Sitka Sound, was the major defining characteristic of Noow Tlein, translated "big fort" (Moss and Erlandson 1992: Table 2). The site has been described as a "rocky prominence on which the Sitkas [Sitka Tlingit] had a small redoubt" (Hopkins 1959; Andrews 1960:24) and as "a fort [that] belonged to the Kiks. ádi clan" (Sealaska 1975:386-387). Warfare and the construction of fortified sites are well known in the ethnographic and archaeological literature of the North Pacific region (Moss and Erlandson 1992). Physiographically, Noow Tlein is typical of the Tlingit defensive positions described by George Emmons in the 1880s and 1890s:

Generally, villages were unprotected, and natural defense positions on bluff headlands or rocky islands near at hand were fortified, to which inhabitants might flee in time of danger... Ordinarily the forts of this people were smaller affairs not surrounding the village, but near at hand, on some rocky island or precipice headland and belonging to a single family, when they might find refuge upon a sudden attack, for the strategy of coast warfare consisted of surprise attacks... and rapid retreats, so their strongholds were not calculated to stand sieges, and were but temporarily occupied when necessity might require [manuscript of George T. Emmons, quoted by Moss and Erlandson 1992:5-6].

-

- Founding of New Archangel

-

Noow Tlein (Castle Hill) was in such a strategic position that it was the first choice for a redoubt location when Aleksandr Baranov, Chief Manager of the Shelikhov and Russian American Company in North America, came to Sitka in September 1799 to established a settlement (Bancroft 1959:429; Lisiansky 1814:155; Tikhmenev 1978:75). Baranov had constructed the Novorossiisk settlement at Yakutat Bay in 1796, but found that the year-round ice free harbor and other conveniences of Sitka offered a better location for a Russian settlement (Tikhmenev 1978:43, 61). Because the hill at Noow Tlein was already occupied, Baranov negotiated with the Kiks.ádi for land six miles to the north on which to build a small fort (Bancroft 1959:387-388; Khlebnikov 1994:1). The settlement constructed there during 1799-1800 was named for the St. Archangel Mikhail (Bancroft 1959:390; Khlebnikov 1994:3).

After Baranov returned to Kodiak in the autumn of 1800, relationships deteriorated between the Sitka Tlingit and the Russians at the Archangel settlement, apparently encouraged by English and American traders (Bancroft 1959:397, 401). During the summer of 1802, the Sitka Tlingit attacked and burned St. Archangel Mikhail, killing 20 Russians and 130 Aleuts (Tikhmenev 1978:65). An English trading vessel rescued several survivors and transported them to Kodiak (Tikhmenev 1978:65), where they gave detailed (albeit slightly conflicting) accounts of the incident (Pierce and Donnelly 1979:134-139; Bancroft 1959:401-420). Kiks.ádi oral history related by Herb Hope states that the attack was a concerted effort of several villages (Houston and Cochrane 1992:3). The site of St. Archangel Mikhail, called "Old Sitka" after its abandonment, is presently a state park.

-

- Battle for Castle Hill

-

Baranov, in his determination to reestablish a Russian presence at Sitka, returned to the area in September 1804 with several vessels and a large force of Aleuts (Bancroft 1959:427-428). Landing near Noow Tlein without hostilities, he occupied the hill, then met with a group of Tlingit, from whom he demanded permanent possession of the bluff (i.e., "Castle Hill") and two additional hostages (Bancroft 1959:429; Lisiansky 1814:155-157). The Tlingit did not consent to Baranov's demands. Instead they rejoined other members of the village who had already moved to a fort which they had recently constructed about a mile to the east, a location that is presently within Sitka National Historic Park.

This location was better protected from cannon bombardment than Noow Tlein, as shallow waters prevented ships from approaching near shore. Assisted by Captain Iurii Fedorovich Lisiansky on the sloop Neva, the Russians attacked the Tlingit fort around the first of October [reported dates vary] (Bancroft 1959:429; Langsdorf 1993:46; Khlebnikov 1994:4; Lisiansky 1814:157). After several days of fighting, the Tlingit abandoned the fort and walked overland, settling in several locations before constructing a fort in the Peril Straits area (Andrews 1960:6; Houston and Cochrane 1992:7; Jacobs 1987:7).

This overland journey, called the "Sitka Kiks.ádi Survival March," was described to Houston and Cochrane (1992:6-8) by Mr. Herb Hope. Unlike the 1802 attack, which involved several villages, the 1804 battle was limited to the Kiks. ádi (Houston and Cochrane 1992:3). Numerous, and sometimes conflicting, accounts of the 1804 battle have been published or passed down through oral history. Nora and Richard Dauenhauer (1990:6- 23) summarized various accounts of both the 1802 and 1804 battles at the 2nd International Conference on Russian America.

-

- Castle Hill: 1805 - 1817

-

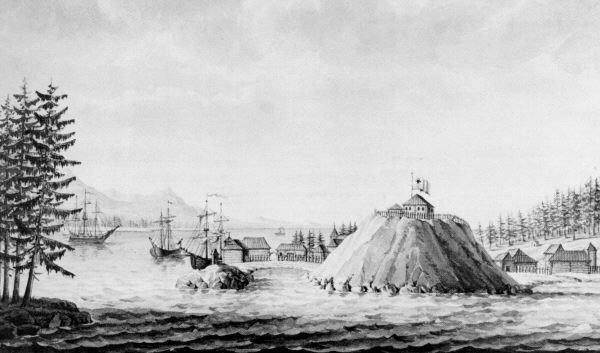

Following the 1804 battle, Baranov began constructing a fortified settlement on the hill at the former Noow Tlein village site. The Russian settlement was named Novo-Arkhangel'sk (New Archangel) to commemorate the first settlement of St. Archangel Mikhail that had been destroyed in 1802. John D'Wolfe (1968:37-38), an American sea captain who spent the winter of 1804-1805 at New Archangel (Sitka), described it as "a singular round piece of land with a flat top, standing out in the sea, and bearing the appearance of a work of human hands." Lisiansky described the settlement during a visit in June 1805:

The next morning I went on shore, and was surprised to see how much the new settlement was improved. By the active superintendence of Mr. Baranoff, eight very fine buildings were finished, and ground enough in a state of cultivation for fifteen kitchen-gardens [Lisiansky 1814:218].

Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov, a founder of the Russian-American Company and Russian government official, arrived at the new settlement on August 26, 1805, where he found "numerous log buildings with stone foundations" (Pierce 1990:419; Tikhmenev 1978:89). In a letter to the Directors of the Russian-American Company dated November 6, 1805, Rezanov presented a detailed description of New Archangel:

There is a lighthouse on one of the islands... The fort is placed on a high rocky promontory, or kekur, extending out into the bay. On the left, half way up the hill, stand enormous barracks with two sentry boxes or turrets for defense purposes. Almost the whole building is built of wood good enough for shipbuilding, on a foundation of logs and cobblestones, with cellars. The building is on a slope and the foundation reaches the water. Close to the barracks is a building containing two stores, a warehouse and two cellars. Next to it is a big shed (balagan) for storing food supplies, built on posts, and under it a workshop. Facing the fort and next to this shed is a goodsized warehouse (sarai) and a store connected with it built of logs and facing the sea. The wharf is between this warehouse and the fort. To the right, at the foot of the mountain, is a building containing a kitchen, a bath and several rooms for company employees. A big log blacksmith shop ninea sazhens long [1 sazhen = 2.13 m or 7 ft.] and five wide is built in three sections on the shore. In the middle section are three forges, in the other two sections -- work shops. Then comes the barn for the cattle. On the hillside above these buildings is another bathhouse. Beneath the fort there is one more bathhouse, with a room. On the hill is a temporary log house five sazhens long and three wide with two rooms and a porch. I have one of these rooms and the two ship apprentices the other. I have enumerated to you many buildings but the men were living in tents till the first part of October. As soon as a roof is placed on a building, they move right in. There are some broken down Kolosh yurts in which live the native workers and Kadiak Americans [Rezanov 1805, in Pierce and Donnelly 1979:153- 154].

The physician and natural scientist Georg Heinrich Langsdorff, who accompanied Rezanov, also described the infant settlement:

The citadel hill had been fortified with cannon. Several Company ships armed with cannon lay at anchor and regular watch was kept day and night... Quarters were, for the most part unfinished and consisted of small rooms without stoves. Their roofs were so bad that the frequent rains continually penetrated them. All of the promyshlenniks had to work every day on the construction of the barracks, warehouse and other quarters that were so desperately needed... Altogether there were almost two hundred people at the settlement, including overseers and assistant overseers, naval officers, master shipwrights, promyshlenniks and Aleuts [Langsdorff 1993:48].

1805 Illustration of Castle Hill by Langsdorf

Baranov and Lisiansky are reported to have made a treaty with a Tlingit envoy in August 1805, after which the chief was presented with a token of friendship consisting of "a staff on which were the Russian arms, wrought in copper, decorated with ribbons and eagle down" (Bancroft 1959:438-439). Lisiansky (1814:221-225) reported that the negotiations took place in Baranov's house, and that pewter medals were also distributed. No Russian accounts which describe the terms of the treaty have been located (Bancroft 1959:439, footnote 29). Tlingit accounts of the treaty have been presented by Alex Andrews and Mark Jacobs, Jr. In a transcribed interview, Alex Andrews (1960:6-7) explains that the Indians did not know the value of the plaque presented by the Russians, and it was believed to be a retribution or atonement for the dead. He further stated that Baranov came to Peril Straights to negotiate the treaty. Mark Jacobs account of the treaty was related in a speech at the Second Russian-American Conference in 1987: -

It was finally decided by the Kiks.adi's to return and sit down for the peace talks. It was at this peace treaty that the present Castle Hill was given to Baranov in exchange for a double-headed eagle badge, which is depicted on the totem pole [in Totem Square, Sitka]. It was explained to mean, "From now on and forever, we will be brothers. You look one way and we the other way." The round knob on the bottom of the totem pole represents Castle Hill. The only piece of real estate ever given to the Russians [emphasis in original document]... The double-headed eagle badge, received from the peace talks, is now in the State of Alaska Museum in Juneau [Jacobs 1987:9].

Despite peace negotiations with the Kiks.ádi, tensions remained between the Russians and the Tlingit of southeast Alaska in general. This culminated in the destruction of the Yakutat settlement in September 1805 (Bancroft 1959:45). The years following the founding of New Archangel were difficult for the settlement's inhabitants. A well-founded fear of the Tlingit prompted the Russians to adhere to military discipline, with cannon always loaded and sentries posted (Bancroft 1959:451; Pierce and Donnelly 1979:157). The settlement was also impoverished due to difficulties in obtaining supplies, a shortage of vessels, and an unsuccessful trade in sea otter skins (Bancroft 1959:450; D'Wolfe 1968:39; Khlebnikov 1994:7). The shortage of supplies would have been more profound if foreign ships had not, after the spring of 1805, began to frequently sail into New Archangel (Khlebnikov 1994:13, 19). Despite the difficulties mentioned above, New Archangel became the seat of the Chief Manager and the center of Russian possessions in America in August 1808 (Fedorova 1973:134). Baranov remained Chief Manager of the Russian-American Company until the end of 1816. Finally, advanced age, failing health, and unfounded charges of mismanagement of company affairs prompted an investigation by Captain-Lieutenant and Cavalier L.A. Hagemeister (Bancroft 1959:510-513; Khlebnikov 1994:26). By authority of the Russian-American Company, Hagemeister took over command of the Russian-American colonies in January 1817, appointing K.T. Khlebnikov office manager at Sitka. In July of the same year Hagemeister made a trip to California for supplies, and placed Lieutenant S.I. Ianovskii in charge of the colony. Hagemeister returned to Sitka in the autumn of 1817, and in November departed for Russia.

-

- Castle Hill: 1817 - 1836

-

Baranov departed New Archangel for Russia on Hagemeister's vessel in November 1818, after paying a farewell visit to the colony at Kodiak (Bancroft 1959:513-514; Pierce 1990:186). He died at sea, however, before reaching his final destination. Ianovskii served as Chief Manager until the renewal of the Russian-American Company charter in 1821, at which time he was replaced by Naval Captain M.I. Murav'ev (Bancroft 1959:534-535). One of Murav'ev's first orders of business was to invite the Sitka Tlingit to return to their former village, separated from the fort by a palisade. Under Hagemeister's management, and that of his interim successor S.I. Ianovskii, virtually all of the buildings from Baranov's tenure were replaced (Khlebnikov 1994:30, 138). Khlebnikov (1994:30) reported that the barracks was so dilapidated that it was on the verge of collapse, for which reason the employees had built five small houses outside the fort. Khlebnikov (1994:138-140) reported new construction for the years 1818 to 1830, as follows:

1818: Tower No. 1, with two stories, octagonal, with eight cannons.

1819: (1) Tower No. 2, two-storied, octagonal, with eight cannons; (2) pier near the shore; (3) windmill.

1820: (1) Chief manager's house in the upper fortress, eight sazhens [56 ft. or 17.04 m] in length; (2) tower No. 3 in the upper fortress, the same size as the others, with six cannons; (3) a battery on the seaside, with eight cannons; (4) lower barracks, divided into three parts by hallways (with a mezzanine on both sides) these rooms can house 80 men, they are nine sazhens [63 ft. or 19.17 m] in length, there are three rooms for officials upstairs; (5) an apartment house, two-storied, nine sazhens [63 ft. or 19.17 m] in length, they house the priest, the doctor, two officials, the office, pharmacy and hospital; (6) house of the office manager; (7) bathhouse for officials; (8) bathhouse for the garrison; (9) spinning (weaving) shop; (10) bakery; (11) a new harbor on pilings to replace the old one, eaten by worms; (12) three stairways to the upper fortress and a reviewing stand; (13) a two-storied arsenal for small arms; (14) gates and a wall for the middle fortress from the barracks to the priest's house, with a battery of two cannons.

1826 to 1828: (1) A three-storied store 18 sazhens [126 ft. or 38.34 m] in length, the lower floor contains a section for storage in general, there are two rooms for storing materials, and two for storing goods and supplies, the central floor is for materials and furs and supplies, the floor under the roof is used for storing various types of goods; (2) a two-storied house for apartments of officials, downstairs there is a barracks, a school, three separate apartments for officials, upstairs - six separate rooms and two kitchens, both buildings are covered with metal roofs.

1830: (1) Two new pilings... for the building of the harbor area; (2) a large warehouse 18 sazhens [126 ft. or 38.34 m] long...; (3) some of the old buildings can still stay up awhile, others are falling apart, these include: in the central fortress: general store, trading store; inside the fort: workshops, blacksmith's shops, quarters for the shop workers and a metalwork shop, the general kitchen, the stable, three kazhims for the Aleuts, the carpentry shop and saw shed [Khlebnikov 1994:138-140].In 1822, the Chief Manager's new residence (begun in 1820) in the fort was finished (Fedorova 1973:222). Its roof was covered with iron from St. Petersburg, and the lower walls and adjacent floors were sheathed with flattened lead to deter rodents (Fedorova 1973:222-223). Only the Chief Manager's house and the barracks were covered by iron. Other buildings were covered with tree bark bartered for from the Tlingits (Fedorova 1973:223). Frederic Litke, who visited Sitka in 1827 described the settlement:

The settlement is at present made up of two parts -- the fortress and the outlying areas. The first encloses the governor's two storied house, situated on the highest point of the rock, at around eighty feet above sea level, surrounded by towers and by batteries armed with thirty-two cannon, which makes it like a citadel... All of the structures in the fortress are company property; they are well maintained, although not without difficulty for the magnificent wood of conifers and saplings used here, because of its poor quality and the effect of the climate, does not last very long. One of the towers along the fortress walls houses the arsenal, with enough firearms and hand arms for over a thousand men, kept in good order [Litke 1987:46].

The Baroness Wrangell, wife of the chief manager in the early 1830s also provided an account of the manager's house:

The town consists of small houses, dwarfed by the imposing appearance of the fort, in which our house plays a great role. It stands on a knoll, surrounded by four small towers, from which cannon look in all directions... [1831 letter from the Baroness Wrangell, quoted by Pierce 1989:30].

By some accounts, apparently based on oral history, the house was constructed of "bricks... acquired from a passing ship," and torn down in 1833 due to damage from an earthquake (Hanable 1975:2). The bricks are described as yellow bricks, engraved "Stenwick," from Holland (DeArmond 1995). Written descriptions of the period mention bricks only in the context of their scarcity, and their use in the manufacture of Russian stoves (Fedorova 1973:223). Also, an 1827 engraving by F. H. von Kittlitz, who accompanied Litke on his voyage to New Arkangel, seems to depict a log or frame building with a gabled roof (Henry 1984:55). By the 1830s, however, the house -- sometimes called the "original castle," was already deteriorating. Wrangell obtained permission from the main office at St. Petersburg to build another, in the meantime moving into the port headquarters (Pierce 1989:32). Construction efforts were generally less profound after 1827, when the shareholders of the Russian-American Company confirmed a decision to transfer the colonial capital back to the Kodiak settlement (Fedorova 1973;143). The transfer did not occur, largely due to a lack of manpower for new construction on Kodiak (Fedorova 1973:145).

-

- Castle Hill: 1836 - 1867

-

1837 illustration of Castle Hill by Belcher Construction of a new two-story residence finally began in November 1836, under the management of the next governor, I.A. Kupreianov (Pierce 1989:32). The structure measured 12 by 7 sazhens (84 by 49 ft., or 25.56 by 14.91 m)(Pierce 1989:32). It is this structure, the largest and last of a series of Russian buildings to occupy the hill, that was popularly called "The Castle." Ironically, it is often referred to as "Baranov's Castle," even though its construction was initiated some 18 years after Baranov's departure from Sitka. By April 1837, workers were ready to place sheet iron on the roof, and work had begun on new towers and batteries (Pierce 1989:32). Kupreianov modified the construction plans to add a small observatory and lighthouse to the pitched roof of the house, said to be visible from a distance of 20 miles (Pierce 1989:32). Captain Edward Belcher, on the British vessel Sulphur, visited Sitka in 1837 while construction was in progress. Although he exaggerated the structure's dimensions, Belcher otherwise described it as follows:

The building is of wood, solid; some of the logs measuring seventy-six and eighty feet in length, and squaring one foot. They half dovetail over each other at the angles, and are treenailed together vertically. The roof is pitched, and covered with sheet iron. When complete, the fortifications (one side only of which at present remains) will comprise five sides, upon which forty pieces of cannon will be mounted, principally old ship guns, varying from twelve to twenty-four pounders. The bulwarks are of wood, and fitted similarly to the ports on the maindeck of a frigate [Pierce and Winslow, eds. 1979:21].

The Castle, which lasted until 1894, has been described in detail by a number of visitors, and graphically documented in a numerous sketches and photographs. Various portrayals indicate that the Castle occupied virtually all available space on top of the hill. The building was outfitted with furniture of sufficient quality to impress foreigners (Pierce 1989:32), and in many ways was the center of social life in Russian Sitka. The Castle was the location of the transfer ceremony through which the United States acquired Alaska on October 18, 1867. The often recounted ceremony has been described by Bancroft as follows:

On Friday, the 18th of October, 1867, the Russian and United States commissioners, Captain Alexei Pestchourof and General L.H. Rousseau, escorted by a company of the ninth infantry, landed at Novo Arkhangelsk, or Sitka, from the United States steamer John L. Stephens. Marching to the governor's residence, they were drawn up side by side with the Russian garrison on the summit of the rock where floated the Russian flag; "whereupon," writes an eye-witness of the proceedings, "Captain Pestchourof ordered the Russian flag hauled down, and thereby, with brief declaration, transferred and delivered the territory of Alaska to the United States; the garrisons presented arms, and the Russian batteries and our men of war fired the international salute; a brief reply of acceptance was made as the stars and stripes were run up and similarly saluted, and we stood upon the soil of the United States [Bancroft 1959:599-600].

There is apparently no precise date when the name "Sitka" began to be used over "New Arkangel," but Bancroft (1959:599 footnote 17) is of the opinion that "Sitka" came into general use sometime around 1847. The name "Sitka" was most likely modified from Sheet'ka, the Sitka Tlingit People's name for their traditional territory (Polasky 1997).

-

- Castle Hill: 1867 - Present

-

Following the transfer of Alaska to the United States, General Jefferson Davis (Chief of American Forces in Alaska) used the Castle as his residence and headquarters (Pierce 1989:42). The building was abandoned in 1877 when the U.S. Army departed Sitka, and was reported to be in dilapidated condition in May 1878 (Pierce 1989:42). During the 1880s the building served as offices for the Signal Service, and is described in the papers of Fred Fickett housed at the University of Alaska, Anchorage archives. The 1890 census reported that:

...the castle or governor's residence has been let fall half to ruin, the ill usage and vandalism of the past ten years leaving it stripped and despoiled of every portable feature of its interior finish and sadly defaced. Different attempts to have the building preserved and repaired for government use have failed entirely, and as the castle plot was not made a government reservation its site may be taken up by any claimant, if the building should burn to the ground. [Eleventh Census 1890:52].

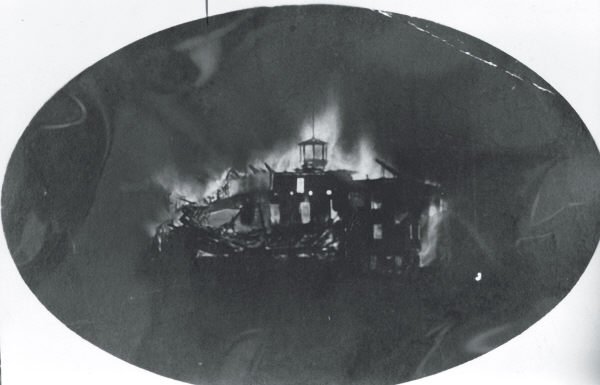

In 1893, the U.S. government began to repair the structure for use as offices. On March 17, 1894, just before officials moved in, however, the building was destroyed by an early morning fire (Pierce 1989:42).

The "Castle" engulfed in flames in 1894.

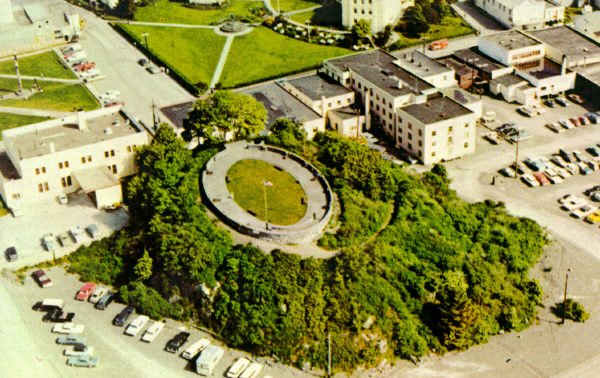

On July 18, 1898, President McKinley reserved Castle Hill for agricultural research and weather service reporting (Pierce 1989:42). On the site of the old "Castle," the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) constructed a building which served as the headquarters of the Office of Experiment Stations in Alaska. Photographs of the facility depict a two-storied frame structure, smaller than the Castle, with columns on the north side and a gabled roof. A map of the facility shows stairs on the north side of the hill in the same location as those present today, as well as a harbor light and water tank on top of the hill (Georgeson and Evans 1899:41). The headquarters was moved to Juneau in 1931, and in 1932 both the Juneau and Sitka offices were closed (Hill 1965:12). A 1939 writer (Colby 1940:169) described the building as a private house owned by the Department of Agriculture. The building was demolished in 1955, after which time the site became a grassy territorial and later a state park (Hanable 1975:2).

On October 18th, 1959, after Alaska was granted statehood, one of the first official raisings of the new 49 star flag took place on Castle Hill at the scene of the 1867 transfer ceremony. In 1962, the site was designated a National Historic Landmark under NHL Criterion 1 as the scene of the formal transfer of Alaska to the United States, the seat of the Russian-American company from 1806 to 1867, and the place where one of the first official raisings of the forty-nine star flag occurred. In 1965, in preparation for the 1967 centennial celebration of the Alaska purchase, a stone wall (parapet) was constructed with spaces for six cannon, six interpretive plaques, and a flagpole (Hanable 1975:2). Also during the 1960s, fill material was placed around the base of the hill to give it its present physiography. Since statehood, the site has been operated as a unit of the Alaska State Parks system, and is the locus of a formal flag raising ceremony on October 18th each year.

-

- Contact History

-

Bibliography

-

Andrews, Alex

1960 Interview with Alex Andrews by George Hall. Transcript on file at Sitka National Historical Park, File SITK 14574/RG33/Box 1/Folder 7.

Ballard, William F.

1996 Letter dated 7/2/96 from William F. Ballard (ADOT&PF Southeast Regional Environmental Coordinator) to Judith E. Bittner (Alaska State Historic Preservation Officer).

Bancroft, Hubert Howe

1959 History of Alaska: 1730 -- 1885. First published 1886. Antiquarian Press, Ltd., New York.Bittner, Judith E.

1996 Letter dated 7/31/96 from Judith E. Bittner (Alaska State Historic Preservation Officer) to William F. Ballard (ADOT&PF Southeast Regional Environmental Coordinator.

Blee, Catherine H.

1985 Archeological Investigations at the Russian Bishop's House, 1981, Sitka National Historical Park, Alaska. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. U.S. Government Printing Office, Denver.

1986 Wine, Yamen and Stone: The Archeology of a Russian Hospital Trash Pit. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Sitka National Historical Park, Alaska. U.S. Government Printing Office, Denver.

Colby, Merle

1940 A Guide to Alaska: Last American Frontier, 2nd edition. Works Progress Administration, Federal Writers' Project. MacMillan Company, N.Y.

Craig, Robi

1997 Specific Comments Concerning the "Data Recovery Plan," transmitted to ADOT&PF by Bob Polasky (STA General Manager) on March 26, 1997.

Dall, William H.

1970 Alaska and Its Resources. Originally published 1870. University Press: Welch, Bigelow, and Co., Cambridge.

Dauenhauer, Nora Marks, and Richard Dauenhauer

1990 The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804, from Tlingit, Russian and Other Points of View. In Russia in North America: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Russian America, Sitka, Alaska August 19-22, 1987, pp. 6-23, edited by Richard A. Pierce. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario; Fairbanks, Alaska.

Deagan, Kathleen A.

1988 Neither History Nor Prehistory: the Questions that Count in Historical Archaeology. Historical Archaeology 22:7-12.

DeArmond, Robert

1995 Interview with Robert DeArmond by J. David McMahan. Tape and transcript on file at the Office of History and Archaeology, Alaska Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation, Anchorage.

Dilliplane, Timothy L.

1980 Excavations at a Possible Colonial Russian Brick-kiln Site. Paper presented at the 7th Annual Meeting of the Alaska Anthropological Association, Anchorage.

1981 Brickmaking in Russian America: Research Results through March 18, 1981. Manuscript on file in the Office of History and Archaeology, Alaska Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation, Anchorage.

1983 The Historical Archaeology of Russian America: A Suggested Research Goal and Strategy. In Forgotten Places and Things: Archaeological Perspectives on American History, compiled and edited by Albert E. Ward, pp. 69-74. Contributions to Anthropological Studies No. 3, Center for Anthropological Studies, Albuquerque, N.M.

1985 Studying Russian America: Research Problems in Need of Attention. In Comparative Studies in the Archaeology of Colonialism, edited by Stephen L. Dyson, pp. 177-183. BAR International Series 233, Oxford, England.

1990 Material Culture and the Frontier in Russian America. In Russia in North America: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Russian America, Sitka, Alaska August 19-22, 1987, pp. 398-406, edited by Richard A. Pierce. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario; Fairbanks, Alaska.

D'Wolf, John

1968 A Voyage to the North Pacific. Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, Washington.

Fedorova, Svetlana G.

1973 The Russian Population in Alaska and California: Late 18th Century -- 1867. Materials for the Study of Alaska History, No. 4, translated and edited by Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario.

Georgeson, C.C., and W.H. Evans

1899 A Second Report to Congress on Agriculture in Alaska. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Office of Experimental Stations Bulletin No. 62, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Hanable, William S.

1975 National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form: American Flag Raising Site (AHRS Site SIT-002). Nomination on file at the Office of History and Archaeology, Alaska Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation, Anchorage.

Henry, John Frazier

1984 Early Maritime Artists of the Pacific Northwest coast, 1741-1841. University of Washington Press, Seattle and London.

Hill, Edward E.

1965 Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Office of Experiment Stations (Record Group 164). General Services Administration, National Archives and Records Service, The National Archives. Office of Civil Archives NC-132, October 1965.

Hope, Andrew

1967 Interview with Andrew Hope. Transcript on file at Sitka National Historical Park, File SITK 14574.

Hopkins, Sally

1959 Sitka and Glacier Bay National Monument, in Traditional Story of the Kik-sadi Clan as Told by Mrs. Sally Hopkins, translated by her son Peter C. Neilson and correlated by George A. Hall. Manuscript on file at Sitka National Historical Park, File SITK 14574 (7 pages).

Houston, Bonnie, and Tim Cochrane

1992 Conversation with Herb Hope September 28, 1992, by Bonnie Houston and Tim Cochrane, National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office. Summary of the conversation, document on file at Sitka National Historical Park RG33/Box 1/ Folder 13.

Jacobs, Mark, Jr.

1987 Speech by Mark Jacobs, Jr., Tlinget Indian, Age 63 3/4 Years. First speaker at the Second Russian American Conference Held in Sitka, Alaska, August 1987. Copy on file at the Office of History and Archaeology, Alaska Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation, Anchorage.

Khlebnikov, Kiril Timofeevich

1994 Notes on Russian America, Part I: Novo-Arkhangel'sk. Alaska History No. 43, translated by Serge LeComte and Richard Pierce, edited by Richard Pierce. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario.

de Laguna, Frederica

1990 Tlingit, in Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast, edited by Wayne Suttles, pp. 203-228. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Langsdorff, Georg Heinrich von

1993 Remarks and Observations on a Voyage Around the World from 1803 to 1807. First published 1812. Alaska History No. 41, translated and annotated by Victoria Joan Moessner, edited by Richard A. Pierce. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario.

Leone, Mark P.

1988 The Relationship Between Archaeological Data and the Documentary Record: 18th Century Gardens in Annapolis, Maryland. Historical Archaeology 24:10-13.

Litke, Frederic

1987 A Voyage Around the World: 1826 -- 1829. First published in 1834. Alaska History No. 29, edited by Richard A. Pierce. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario.

Lisiansky, Urey

1814 A Voyage Round the World in the Years 1803, 4, 5, and 6, Performed by Order of His Imperial Majesty Alexander the First, Emperor of Russia in the Ship Neva. Hamilton, Weybridge, and Surrey, Londan. Facsimile reprint by the Gregg Press, Ridgewood, New Jersey.

McMahan, J. David

1996 1995 Cultural Resources Investigation at Baranof Castle State Historic Site (SIT- 002): Summary of Findings and Determination of Eligibility (Project TEA-000- 3[43]). Office of History and Archaeology, Alaska Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation, March 1996.

Moss, Madonna L., and Jon M. Erlandson

1992 Forts, Refuge Rocks, and Defensive Sites: the Antiquity of Warfare Along the North Pacific Coast of North America. In Maritime Cultures of Southern Alaska: Papers in Honor of Richard Jordon, edited by Madonna Moss and Jon Erlandson. Arctic Anthropology Fall 1992.

National Park Service (NPS)

1991 How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation. National Register Bulletin 15, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Interagency Resources Division. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Pierce, Richard A.

1989 Reconstructing "Baranov's Castle." Alaska History 4(1):27-44, the Alaska Historical Society, Spring 1989.

1990 Russian America: A Biographical Dictionary. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario.

Pierce, Richard A., and Alton S. Donnelly (editors)

1979 A History of the Russian American Company, Volume II. Materials for the Study of Alaska History, No. 13. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario.

Pierce, Richard A., and John H. Winslow

1979 H.M.S. Sulphur on the Northwest and California Coasts, 1837 and 1839: the Accounts of Captain Edward Belcher and Midshipman Francis Guillemard Simpkinson. Materials for the Study of Alaska History, No. 12, edited by Richard A. Pierce and John H. Winslow. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario.

Polasky, Bob

1996 Summary of Cultural Committee Meeting: Castle Hill 2/15/96. Attachment to a letter from Bob Polasky, Sitka Tribe of Alaska, to the Sitka Historic Preservation Commission. The letter is dated May 11, 1996.

1997 Letter from Bob Polasky (STA General Manager) to David Hawes (ADOT&PF), transmitting STA comments on the Castle Hill Draft Research Design.

Reed, Alan D.

1994 Screening Thoughts. The Grapevine 4(1):5-6.

Sealaska Corporation

1975 Native Cemetery and Historic Sites of Southeast Alaska (Preliminary Report), October 1975. Report prepared for the Sealaska Corporation (Juneau) by Wilsey and Ham, Inc., Consultants, Seattle.

Shinkwin, Anne D.

1977 Archeological Excavations at the Russian Mission: Sitka, Alaska -- 1975. National Park Service Contract No. CX-9000-5-0075, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

South, Stanley

1977 Method and Theory in Historical Archeology. Academic Press, New York, San Francisco, and London.

1988 Whither Pattern? American Antiquity 22:225-28.

Spencer-Wood, Suzanne M.

1987 Consumer Choice in Historical Archaeology. Plenum Press, New York and London.

Staski, Edward

1982 Advances in Urban Archaeology. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, Volume 5, edited by Michael B. Schiffer, pp. 97-135

Tikhmenev, P.A.

1978 A History of the Russian-American Company, translated and edited by Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly. University of Washington Press, Seattle and London.

1979 A History of the Russian-American Company, Volume II. Materials for the Study of Alaska History, No. 13, translated and edited by Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly. The Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario.

Townsend, Jan, John H. Sprinkle, Jr., and John Knoerl

1993 National Register Bulletin 36: Guidelines for Evaluating and Registering Historical Archeological Sites and Districts. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Interagency Resources Division, National Register of Historic Places, Washington, D.C.

Williams, Jack, and Anita Cohen-Williams

1997 Computerized letter to the Historical Archaeology discussion group "HISTARCH" on January 24, 1997. Ref. HISTARCH@ASUVM.INRE.ASU.EDU.

Wrangell, F.P.

1980 Russian America Statistical and Ethnographic Information, edited by Richard A. Pierce. Originally published 1839 in German. Materials for the Study of Alaska History No. 15, Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario.

Zippi, Pierre A.

1995 Palynological Analysis of Samples from Unalaska Exhumed Burial Site. Appendix I in Final Report on the Analysis of Human Remains and Grave Associations, Case H94-020: City of Unalaska, by J. David McMahan and Rachel Joan Dale, Alaska Office of History and Archaeology, January 1995. Prepared for the Unalaska Department of Public Safety. Unpublished report on file at the Office of History and Archaeology, Alaska Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation, Anchorage

-