Invasive Plants and Agricultural Pest Management

Welcome to Alaska's Invasive Plant Program. Our program coordinates prevention, outreach and management strategies for invasive plant issues through collaboration with land managers, agencies, organizations and policy makers across Alaska. These efforts are guided by the implementation of our Strategic Plan and relevant noxious weed regulations and policies. Our goal is to help keep Alaska's pristine landscapes and natural resources free from impacts of noxious and invasive plants.

PMC Programs

- PMC Home Page

- Horticulture

- Industrial Hemp

- Invasive Plants

- Plant Pathology

5310 S Bodenburg Spur

Palmer, AK 99645

Phone: 907-745-4469

Fax: 907-746-1568

Mon. - Fri.

8 a.m. - 4 p.m.

Click Map For Directions

View Larger Map

Notices

Prunus padus and Prunus virginiana Quarantine

Exterior Quarantine of Aquatic Invasive Weeds

Any intentional movement of quarantined species, except for the purpose of identification, must be permitted through the Division of Agriculture (11 AAC 34.145; 11 AAC 34.150). A written request for such permit may be sent to the Director by completing the transport request form below, either online or via mail.

Complete and submit the Transport Request Form

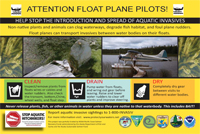

Note: The recent quarantine for five aquatic invasive plants DOES NOT prohibit the use of boats, float planes or other recreational activity in Alaska and does not include the inadvertent transportation or distribution of aquatic plants by floatplane or boat. It DOES prohibit the importation, sale and intentional transport of quarantined species. To help protect Alaska's pristine waterways, always clean, drain and inspect your recreational equipment and follow these guidelines to prevent further spread.

Quarantined Aquatic Plants

The following freshwater, aquatic, invasive plants have the potential to impact freshwater resources and fish habitat in Alaska through the degradation of fish habitat, displacement of native flora and fauna, reduction of recreation and transportation access, and reduction of waterfront property values. Prohibiting the importation, sale and transportation of these species will help prevent new infestations in the state and help protect Alaska's natural resources.

The accidental or deliberate introduction of the following species to Alaskan waters can lead to the formation of dense mats that can drastically alter a water body's ecology. These species have historically been popular as aquarium plants and some can still be found in stores or classroom science kits today. Once established, these species can spread from water body to water body by natural water flow or human or animal assisted movement of plant parts.

- Waterweed

- Hydrilla

- Brazilian Elodea

- Eurasian Watermilfoil

(Elodea canadensis, E. nuttallii): Both waterweed species have been found growing in a limited number of Alaskan waters. Management efforts are being implemented to address the current infestations and prevent new introductions.

Elodea has leaves in whorls of 3 (occasionally 4) around a lighter green stem. The small leaves can be 6-15 mm long and 1.5dž mm wide. Plants often grow in tangled masses. The plants readily break into fragments that can float to new locations and re-root.

(Hydrilla verticillata): Once a staple of the aquarium trade, Hydrilla is now well-established in water bodies in the lower 48 where management costs millions of dollars each year. From 1980 to 2005, Florida alone spent $174 million on Hydrilla control. Hydrilla has NOT yet been found in Alaska.

Hydrilla closely resembles both the Brazilian Elodea and the Waterweed species. It can be distinguished by the presence of tubers in the soil. Hydrilla has leaves in whorls of 5 with small serrations on the leaf edges. Hydrilla can grow an inch a day to fill a waterbody, crowding out ecologically important native species.

Hydrilla produces structures called turions and tubers which are the key to its success. The turions are produced along the stem and break free from the parent plant to drift and settle elsewhere to start new plants. Tubers are small, yellow or whitish, potato or pea-like structures that form underground at the end of the roots. These structures can remain dormant in the soil for several years before sprouting. One square meter of Hydrilla can produce 5,000 tubers!

(Egeria densa): Brazilian Elodea is a popular aquarium plant and can be found for sale in pet and aquarium stores under the name Anacharis or Elodea. It has NOT yet been found in Alaskan waters.

Brazilian Elodea looks like a much larger, more robust version of the waterweed species (Elodea canadensis, E. nuttallii). Brazilian Elodea leaves are minutely serrated and arranged in whorls of 4-8 around the stem toward the middle and upper parts of the stem, while the lower leaves are in whorls of 3. The leaves are about 1-3 cm long and up to 5 mm wide. Brazilian Elodea infestations have major economic impacts, outside of its native range in Brazil, in places like South Carolina, New Zealand and Washington state.

(Myriophyllum spicatum): Eurasian Watermilfoil was once commonly sold as an aquarium plant and is now regulated in most states across the country. Eurasian Watermilfoil is considered one of the worst aquatic plant pests in North America. It has NOT yet been found in Alaskan waters.

Eurasian Watermilfoil has feather-like, 2-4 cm underwater leaves arranged in whorls of 4 around the stem. Leaves are often square at the tip and often have more than 14 leaflet pairs. Eurasian Watermilfoil reproduces very successfully through fragmentation, where small pieces can drift, settle and form new plants. Once established, it is extremely difficult to remove.

Alaska has a native Northern Milfoil (Myriophyllum sibiricum) which has fewer than 14 leaflet pairs per leaf and generally has stouter stems and leaves that do not collapse when out of water.

Help Prevent the Spread

Click the images to enlarge

REPORT IT!

1-877-INVASIV (468-2748)

Invasive Weeds and Agricultural Pest Coordinator

907-745-4469